Introduction

Version

française >

Christine Develotte, « Introduction », Interactions and

Screens in Research and Education (enhanced edition), Les Ateliers

de [sens

public], Montreal, 2023, isbn:978-2-924925-25-6, http://ateliers.sens-public.org/interactions-and-screens-in-research-and-education/introduction.html.

version:0, 11/15/2023

Creative

Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The volume Interactions and Screens in Research and Education presents a self-reflexive research project that was conducted in and on a doctoral seminar focused on Multimodal Screen Interactions (or IMPEC as per the French acronym). This introduction is written in the first person as it tries to elucidate the choices I made as director of this seminarGiven the collegial mode of functioning that will be explained further on, first person singular and plural will be used alternately in this introduction.↩︎. It aims to specify the goals, the genesis and the theoretical and practical grounding of research that was conducted as a collective project under my leadershipThis “Digital Presences” research project has benefitted from the financial support of the ASLAN Labex since 2018.↩︎.

The two main goals of this research are related to the specific nature of the digital environment on which and in which we work:

The analysis of a concrete research training seminar that was both face-to-face (on site in Lyon) and remote (via a videoconferencing platform and telepresence robots), leading to a reconceptualisation of interactions related to experience in a hybrid context.

The positioning of this study in favour of open science that forms part of the digital humanities and new scholarly formats that are currently being developed. Ultimately, the data gathered will thus be available to the scientific community and the results will be published in different forms, digital forms in particular.

The context of research on Screen-based Multimodal Interactions (IMPEC: Interactions Multimodales Par ECran)

I will start by describing the research context surrounding this volume: both the prior or concomitant studies that inspired the volume, and how it is situated in the continuity of my own work.

Multidisciplinary inspirations

Undoubtedly as a result of my own multidisciplinary academic backgroundI began by studying literature, then psychology and sociology, and then applied linguistics, combined with a period of research in communication sciences.↩︎, the sources of inspiration for my research are not restricted to a single domain. I provide four examples here that have had the greatest influence on this project.

Mauro Carbone (philosophy)

Mauro Carbone and his “Vivre par(mi) les écrans” research group have been examining how we live with screens from a phenomenological perspective since 2013. He posits that screens, which today are the habitual interface for our relationships to the world, to others and even to ourselves, produce “regimes of visibility” (Carbone, Dalmasso, and Bodini 2018, 23).

Regimes of visibility

“Regimes of visibility” evoke impersonal powers that are able to direct or divert light and thus our gaze, to show and to conceal, to distribute surface and depth, to assign centrality and marginality, to assert similarities and differences … powers that “pre-mediate” our vision (Carbone, Dalmasso, and Bodini 2018, 24–25).

In our situation of communication combining screens of different sizes in artefactsThe notion of “artefact” designates any non-animated object without specifying its function. For more information, check “Theoretical and methodological framework for visual reflexive ethology”, section “Remote communication artefacts and their positions in the room”.↩︎ or as part of a platform, the premediation of the presence of remote participants is clearly apparent. Participants are not featured in the same way depending on the screens that broadcast their presence. As Francesco Casetti (2018, 53) reminds us:

The screen only becomes a screen from the point of view of the device with which it is associated, and which links it to the set of practices that produce it as such.

And because different telepresence screens are associated with specific affordances, they permit certain possibilities of expression or not: for example, participants using the Adobe Connect platform can express themselves in chats, whereas participants using robots cannot. We can thus agree with Carbone when he says that “a certain ‘regime of visibility’ is intertwined with a certain ‘regime of sayability’ by virtue of directing the attention and inattention both of our gaze and of our discourse” (Carbone, Dalmasso, and Bodini 2018, 25).

One of the goals of our research is to show which ethos and discourse are associated with each screen. Reciprocally we aim to study how the participants in-situ address remote participants depending (or not) on the different screens mediating their presence.

Louise Merzeau (information and communication sciences)

Louise Merzeau calls the advent of digital technology an “environmental transformation that affects structures and relationships ... [and that] calls into question the conceptual models that serve to formalise them” (Merzeau 2009, 23). This calling into question of conceptual models is also needed when considering exchanges via screens (videoconferencing or telepresence robots). This is the point of view adopted in my earlier work (Develotte, Kern, and Lamy 2011 ; Kern and Develotte 2018) and one of the crucial goals of this project is to propose conceptual innovations based on multidisciplinary analysesCheck “Theoretical and methodological framework for visual reflexive ethology”.↩︎ of the data gathered.

Digital presence according to Louise Merzeau

Militating in favour of an informational commons and the free dissemination of knowledgeShe thus took part in the #connaissancelibre2017 campaign, meaning #freeknowledge2017.↩︎, Merzeau examined the digital presence of individuals in networks, on the web in particular. For her:

… presence is deployed in time: it is irreversible and unpredictable, i.e., fundamentally social, even if the traces by which it is manifested are processed by machines (Merzeau 2010, 32–33).

The remote presences that we study here - mediated by the online platforms that make them visible, sometimes disrupt them, and record them - are anchored in a socio-educational situation to which they give meaning. The interaction between these different presences was the focus of the seminar.

Susan Herring and Marie-Anne Paveau (linguistics)

In 1996, Susan HerringAs a leading figure in linguistic studies of online communication, Herring was the editor-in-chief of the journal Computer-Mediated Communication from 2004 to 2007 and then of the journal Language@Internet.↩︎ launched the field of linguistic research on “computer-mediated communication” (1996).

Multimodal interactive communication

Since then, she has studied various aspects of online written discourse and has published a classificatory schema of computer-mediated discourse on the basis of blog data, with the goal of synthesising and articulating the technical and social aspects that influence discourse (Herring 2007). Noting the multimodality that has come to enrich the various modes of online communication, she has more recently suggested focusing on “multimodal interactive communication” in order to account for two emerging phenomena in digital communication: multimodal interactive platforms and robot-mediated communication.

She provides a new synthetic schema of multimodal interactive communication that goes from email, via the telepresence robot, to the 3D immersive platform avatar (Herring 2015).

Like Susan Herring, French linguist Marie-Anne Paveau has mainly studied written digital discourse. She presents her work as “a response to the need to invent new concepts, tools and limits to describe how forms of discourse native to the internet function from a qualitative and ecological perspective”. Paveau defines “discourse native to the internet” as “the set of all verbal productions that are elaborated online, regardless of the devices, interfaces, platforms or writing tools used” (Paveau 2017, 8). She posits that “native digital language productions” (2017, 8) involve a non-human dimension (machine, software, algorithm...) that informs and shapes what can be said (2017, 11).

This conceptualisation of digital discourse is embodied in the expression “discursive technology”.

Discursive technology

Paveau defines “discursive technology” as

the totality of the processes of transforming language into discourse in a digital environment, which are based on language production devices consisting of online or offline IT tools (software programs, APIs, CMSs) on devices (computers, telephones, tablets) (Paveau 2017, 335).

The anteposition in French of the term “technology” (technologie discursive) underscores the paramount importance of this dimension in discourse that is indelibly marked by it. This is what we will describe in this volume: the manner of speaking and interacting with remote participants is unique and depends on the specificities and affordances of each artefact.

Gregory Bateson (anthropology of communication)

There is nothing new about having a multidisciplinary team study a common corpus. This adventure was undertaken in The Natural History of an Interview (McQuown 1971) recounted by Wendy Leeds-HurwitzLeeds-Hurwitz’s study was discussed in greater detail in one of the first presentations of our research during the seminar on “Méthodes Pour La Recherche Autour De La Communication Multimodale ‘Artéfactée’” (meaning: As seen from the perspective of the IMPEC seminar: Methodological Choices for Reflexive Research).↩︎ (1988). I will discuss some of the elements of this work below as well as its connections to the present project.

This multidisciplinary projectWhich initially brought together two psychiatrists, two linguists and three anthropologists.↩︎ that would represent a turning point in research in social communication was launched in 1955-1956 at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University.

Natural history of an interview

The aim of the project was to define the potential contribution of linguistics to the study of psychiatric interviews. Upon joining the group, Ray Birdwhistell suggested that Bateson, who used video recordings in his research, provide the filmThe film was called “Doris” and featured three people: Doris, Bateson, and a child.↩︎ that would serve as the basis for the group’s work. In Bateson’s words:

We start from a particular interview on a particular day between two identified persons in the presence of a child, a camera and a cameraman. Our primary data are the multitudinous details of vocal and body action recorded on this film. We call our treatment of such data a “natural history” because a minimum of theory guided the collection of the data (Bateson 2000, 118).

The group selected scenes to analyse but then the group broke up. The work was not completed until 1968, but it would turn out to be too expensive to publish it; the study was finally included in a University of Chicago microfilm series in 1971. Fifteen years of analysis and work ended up being published in a medium that is difficult to consult.

From this pioneering project in communication, I chose not to define a prior theoretical orientationI suggested that the general research framework be based on the naturalistic approach developed by Jacques Cosnier under the heading of “comprehensive ethology”.↩︎, to respect the ecology of interactions and to open up the data to a multidisciplinary team of researchers. This project also taught the importance of setting a precise research schedule from the start and involving all the members of the group. Bateson, who was the only researcher present in the film, was in fact very uneasy about having his postural, mimetic and gestural behaviour dissected on screen by his colleagues. In our project, all the participants were involved in the same undertaking, took the same risks (in terms of their image) and made the same commitments.

My research on screen-based interaction

I began to work on screen-based interaction in 2002, usually in educational contexts, before turning to synchronous online conversation starting in 2006.

Describing online conversation

The research project entitled Décrire la conversation (“Describing conversation”; Cosnier, Kerbrat-Orecchioni, and Bouchard (1987)) was inspired by The Natural History of an Interview, and in 2006, as a next logical step, I invited my colleagues to join me in co-editing the volume entitled Décrire la conversation en ligne (“Describing online conversation”; Develotte, Kern, and Lamy (2011)).

In this volume, using a common corpus given to different researchers to study, we were able to show that desktop videoconferencing communication had revisited the principles revealed for face-to-face conversation. Interactional synchrony, for example, cannot be separated from the quality of the digital flow and from distortion of the audio or video signal, which induces a necessary adjustment on behalf of the speakers.

Specificities in online conversations

The specificities identified in online conversations include:

- The coexistence of different spaces: the screen and the two locations in which the online exchange takes place, which sometimes interfere with each other, disrupting the online conversation (i.e., when someone comes into the room).

- More overlapping speech: people speak over one another more frequently than in face-to-face conversation (i.e., due to low data transfer speeds at the time).

- Accentuated facial expressions and gestures: Interlocutors accentuate their facial expressions and gestural behaviour more than in a face-to-face situation (i.e exaggerated smiles and facial expressions).

Directly following up on Décrire la conversation en ligne, the aim here will be to understand how this polylogical situation changes participants’ behaviour in comparison to the dialogical situation studied earlier. The second aim will be to analyse the effect of the simultaneous use of various means of communication.

Ethical dimensions of the research

Filming interlocutors inevitably leads to the problem of accessing “natural” data.

Ethical dimensions

In Conversation Analysis (CA), interaction or data is deemed “natural” if it is recorded in the social context in which it ordinarily takes place, and if we can presume that it would have occurred in the same way in the absence of any research objective, as opposed to “elicited” or “contrived” interactions/data that would not exist “naturally”, i.e., independently of the research objective (Kerbrat-Orecchioni 2011, 175).

The research carried out for Décrire la conversation en ligne involved “elicited” data: the eight interlocutors who spoke with one another online were paidSo were the speakers asked to contribute to the previous book Décrire la conversation (Kerbrat-Orecchioni 2011).↩︎ in order to acquire the right to use their images for scholarly purposes. The need to obtain this authorisation for research based on studying the faces of interlocutors is indeed an obstacle to studying groups in an ecological way. This obstacle is what gave rise to the idea of studying ourselves as a group. The difficulties involved in obtaining the authorisation of each participant would disappear, since the group as a whole would thus benefit scientifically. We therefore opted for this opportunity to study interaction in both face-to-face and remote settings, and we had consent forms drawn up for everyone to sign.

We believe self-reflexive researchCheck “Theoretical and methodological framework for visual reflexive ethology”.↩︎ to be closer to “natural” data rather than “elicited” data. In our case, even if having the ultimate goal of studying interactive behaviour could potentially influence participants’ behaviour, the doctoral seminar held a genuine educational function of training doctoral students.

Promoting open science

In Décrire la conversation en ligne, the video data we used to study online conversations were then included in the CLAPI databaseCorpus de Langue Parlée en Interaction (Corpus of Spoken Language in Interaction).↩︎ which was developed by the ICAR laboratory and is accessible to all researchersInteractions, Corpus, Apprentissages, Représentations (Interaction, Corpus, Learning, Representations).↩︎. Today, ten years later, as open science has become more widely accepted, we naturally adopted the prospect of sharing the data associated with our project.

Moreover, an encounter with Marcello Vitali-Rosati in 2018 gave shape to the idea of publishing our results in digital form – an idea which we intuitively had thought about, but which we did not know already existed. This immediately seemed the best way to exploit the multimodal nature of our video dataCheck “Theoretical and methodological framework for visual reflexive ethology”.↩︎.

The IMPEC research group

The IMPEC group is a working group that was formed in 2013 based on researchers’ shared interest in screen-based interactions. The group is committed to a multidisciplinary approach, mainly involving applied linguistics, cognitive sciences, and communication sciences. The group studies a variety of situations, both individual (i.e., telephone, video games, etc.) and collective (the use of screens in face-to-face or remote contexts, such as talks, webinars, network games, or museum visits). These situations can occur within a professional setting with computer screens, specific screens (control screens), and in various private contexts, and may involve the general public or a particular audience (i.e., children, young adults, seniors). These situations are usually multimodal in a broad sense; in other words, they connect the multimodality that emerges between people (verbal, paraverbal and non-verbal) and the multimodality present in any type of content (i.e., text, audio, still and moving images) visible on screens.

The group organises its work around a biennial conference and a seminar which I coordinateThe videos both of the conferences and of the seminar are freely available on the IMPEC website.↩︎.

The hybrid IMPEC seminar

The aim of this monthly seminar is to provide scientific support to the doctoral students I supervise. The seminars help to stimulate the students’ critical thinking by involving guest researchers, in addition to providing the students with the opportunity to present their ongoing work. The majority of the doctoral students involved were pursuing thesis topics connected to digital communication, usually in the context of education. Since some students lived too far away to attend the seminars physically, we started using videoconferencing with a computer placed in the middle of the table in the seminar room. Although this improvised system did allow participants to attend remotely, it was not very convenient. The participants in-situ had to remember to move the computer so that the webcam was always pointing in the right direction for the remote participants, and the latter sometimes found themselves looking at a whiteboard or in some other insignificant direction.

From videoconferencing to the “Digital presence” project

In 2016, we tried both to improve the technical set-up and to involve the set-up in the construction of a corpus suitable for studying different aspects of screen-based interactions, which had been the focus of the seminar from the start.

The initial idea was thus to continue to host remote participants using various types of devices or artefacts in order to analyse the effects of the different autonomy of the artefacts on the dynamics of the seminar.

Digital environment

We thus starting using various technological devices in our doctoral

seminar, including a Beam robotThe Beam robot

was not chosen specifically for this project but was already being used

on campus when we started the research project. We therefore took

advantage of its presence at the IFÉ

(Institut Français de l'Éducation, or the French Institute for

Education). The Beam robot is

1m58 tall and is equipped with a screen that allows the participant's

face and chest to be seen while its user is piloting it remotely. In

addition, its wheels allow the robot to move autonomously through

space. Read

more.

Our seminar participant Dorothée

Furnon wrote a doctoral thesis on the use of the Beam robot in

education. She thus facilitated its inclusion in the seminar by helping

users familiarise themselves with it.↩︎, a Kubi robotThe Kubi

robot is an iPad that works with Skype and that

is connected to a rotating base that allows it to be turned back and

forth and up and down. Read

more.↩︎ and a videoconferencing

platform – either Adobe

Connect, Google

Hangouts or Skype. The

platforms varied from session to session according to whether a shared

document was needed or not.

A remote-controlled webcam was used to change direction and zoom in on what was happening during the seminar to make it easier for remote participants to see over Adobe Connect.

The polyartefacted doctoral seminar

Here, I will present the project participants and the characteristics of the seminar. A more precise description of the tools of communication and their affordances will be provided in the chapter “Theoretical and methodological framework for visual reflexive ethology”.

Participants

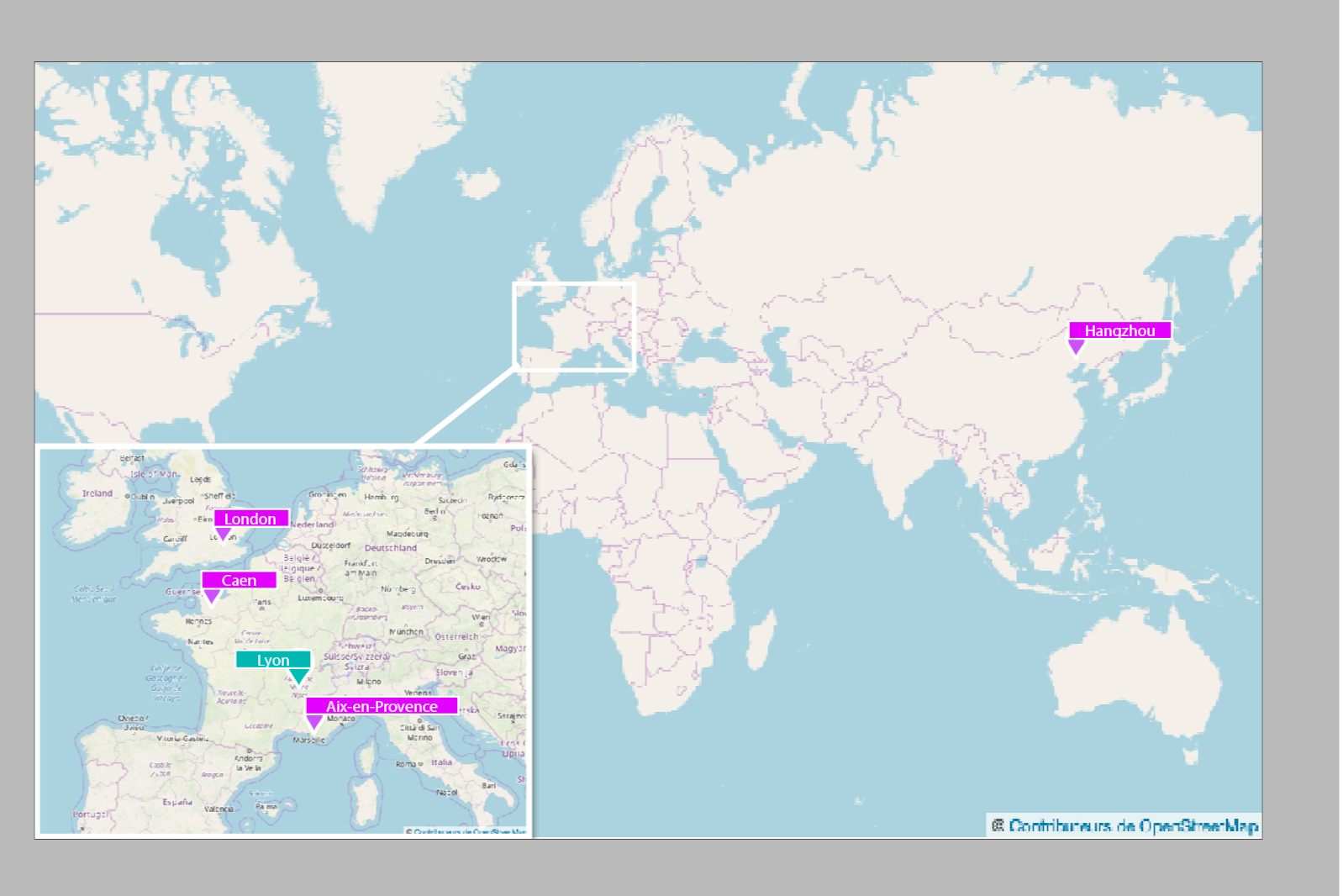

The participants in the doctoral seminar were either in Lyon or in different connected places around the world.

Seminar participants 2016-2017

The 16 people listed in this table participated in the research project on some level or another, with varying degrees of involvement at different times. The group was mixed from several points of view: it was international and each of its members had a different level of competency in using the artefacts (ranging from no experience to mastery).

The second column shows five people (indicated by a -), who physically attended the seminars and who were thus filmed. These people form part of our corpus, and though they may have conducted studies related to this data, they did not participate in the collective writing of this book.

| First name | Authors of the book | Status (time of collection) |

Age | Research Field |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amélie | X | PhD student | 35-40 | Applied Linguistics |

| Caroline | X | Postdoctoral researcher | 35-40 | Applied Linguistics |

| Christelle | X | Associate Professor | 45-50 | Applied Linguistics |

| Christine | X | Professor | 60+ | Applied Linguistics |

| Dorothée | X | PhD student | 30-35 | Education Sciences |

| Françoise | - | Professor | 55-60 | Education Sciences |

| Jacques | - | Honorary Professor | 60+ | Information and Communication Sciences |

| Jean-François | X | Associate Professor | 50-55 | Applied Linguistics |

| Joséphine | X | Associate Professor | 45-50 | Applied Linguistics |

| Liping | - | Associate Professor | 40-45 | Applied Linguistics |

| Mabrouka | X | Associate Professor | 45-50 | Information and Communication Sciences |

| Morgane | X | PhD student | 25-30 | Applied Linguistics |

| Prisca | - | Master 2 | 40-45 | Applied Linguistics |

| Samira | X | Temporary teaching and research associate (ATER) | 30-35 | Applied Linguistics |

| Tatiana | X | Associate Professor | 45-50 | Applied Linguistics |

| Yigong | - | PhD student | 25-30 | Applied Linguistics |

The columns in the middle show the various academic ranks and

ages of the team members. The team was intergenerational and included

three disciplines (right column); the prevalence of applied linguistics

refers to my home discipline and to the people scientifically related to

me (i.e students, doctoral students, or former doctoral students). The

bold elements in the left column represent an interpersonal bond between

some of the participants and myself. This is an important element as

these links that were established over several years prior to the

project form the basis for a socio-emotional stability of relationships

within the group. Moreover, I knew the “external” colleagues who were

invited to join the team, since I had already collaborated with

them.

Characteristics of the seminar

Since the seminar is dedicated to doctoral students, I attach great importance to the working atmosphere so that younger participants feel comfortable expressing themselvesI myself attended doctoral seminars as a doctoral student in which only senior researchers spoke and I never dared to intervene. Here, I tried to do the opposite by creating a space for congenial exchanges.↩︎. Benevolence is a word that I often use and that I try as much as possible to put into practice. For me it is essential that any question can be asked and all points of view can be expressed without anyone having to fear being judged by the other participants. The adopted policy on the dynamics of exchanges also led me to limit my own speaking time and to express myself more concisely to provide more time for doctoral students and less experienced participants.

In addition, I tried to conduct the research project so as to provide the doctoral students with a scientific experience as part of their doctoral training. In that perspective, the doctoral students were involved in a research project that was not exactly their own, but they could draw inspiration from the project’s theories and methodologies. This seminar thus links training FOR research to involvement IN research, fostering a form of teaching based on lived experienceThis view echoes with the projects that I previously developed in language didactics for teaching a language by way of interpersonal exchanges among students (Develotte 2008).↩︎. The seminar also attempts to apply the concept of Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotski 1985) by involving colleagues of different academic ranks in different exchanges.

Finally, we prioritised the idea of developing what Richard Kern and I have called a “nurturing matrix” (Kern and Develotte 2018, 9): a matrix that encourages collaboration among participants. Ensuring that all the participants were involved in the scholarly adventure in which I had invited them to take part was one of the main motivations for fostering collaboration in the different stages of our research: during the seminar, during the development of the research project, and during the process of writing this bookCheck “Theoretical and methodological framework for visual reflexive ethology”.↩︎.

Work programme

I planned a work schedule spread out over four years in response to my painful past experience of collective research projects that were inordinately extended in time and that ended up exhausting the interest and energy of the researchers. The four-year duration required us to adopt an intense rhythm, which was sometimes a little difficult to maintain. Nevertheless, the variety of the tasks in our timetable held participants’ interest and maintained their involvement. Moreover, as our research topic has been evolving very rapidly due to improvements in technical means, the objective was also to reduce the time separating the group’s lived experience and making the research results available to the scholarly community. Finally, the above-mentioned encounter with Marcello Vitali Rosati, which was decisive for the editorial choices made for this work, allowed us to demarcate the different phases of the proposed schedule.

Choice of chapters

The writing of the different chapters in this book took place in two stages, which are reflected in the two-part presentation below. First, we present three thematic chapters covering aspects that initially seemed to be the most salient for the purposes of our research; then three other intersecting chapters, which often draw on the results of the previous chapters.

Dimensions involved in polyartefacted situations

The three aspects that were chosen at the outset are attention, corporeality and politeness.

Jean-François Grassin, Mabrouka El Hachani, Joséphine Rémon and Caroline Vincent wrote the first chapter entitled “Attentional affordances in an instrumented seminar”. This chapter examines how attention is reconceived within the seminar in question as a dual attentional set-up, in its material construction of space and in its relational construction. The analysis focuses on sequences of the co-construction of attention within the specific horizon of expectation of the seminar, which is itself modified by the technological set-up.

The second chapter, written by Samira Ibnelkaïd and Dorothée Furnon, considers the technobodily modalities of enacting intersubjectivity and reveals that participants structure their perception and action through different states of mediation: “demediation”, “remediation” and “immediation”. Participants manage these states of mediation by embodying specific roles in the interactions, such as “procurators”, “witnesses” and “sentinels” through distributed agency. The latter gives rise to phenomena of reification of the animate and of personification of the artefact, leading to the enactment of an artifacted intercorporeality.

The third chapter by Amélie Bouquain, Tatiana Codreanu and Christelle Combe deals with politeness using the microsociological theories of Erving Goffman (1974) and the analysis of online conversation (Develotte, Kern, and Lamy 2011). It revisits these notions, which are simultaneously linguistic, transsemiotic and cultural, and reveals new norms of politeness in the context of artefacted interactions.

The diachronic evolution of experience

The second part of the volume undertakes a review of the dimensions of the polyartefacted seminar that take on meaning experientially over time.

The chapter “Autonomy and artefactual presence in a polyartefacted seminar”, written by Amélie Bouquain, Christelle Combe and Joséphine Rémon, analyses the effects of presence via a comparative study of the potentialities of telepresence systems. Depending on the interactional co-construction undertaken by the participants, effects of presence of devices define an artefactual or an interactional presence around issues of autonomy of movement, visual and sound ajustement, stealthy presence and forced presence.

Samira Ibnelkaïd and Caroline Vincent examine “Digital bugs and interactional failures in the service of a collective intelligence”. This chapter is based on the analytical results of the thematic chapters, which are related to a semantic study of the final assessment questionnaires. The chapter reveals the co-construction of a form of collective intelligence and the enacting of a group ethos that does not necessarily reduce situations of technical bugs but instead reinforces a feeling of personal efficacy (Bandura 1980) in the individual and collective capacities of remediation.

Finally, Morgane Domanchin, Mabrouka El Hachani and Jean-François Grassin consider the polyartefacted doctoral seminar and its potential for research training. This last chapter regards the seminar as a space of doctoral training and, more precisely, the construction of the ethos of four doctoral students based on identifying the traces of their investment during the different phases of the seminar. Moments of collaborative learning are classified by way of a visual schema illustrating the potential acquisition of technical and scholarly competencies. The aim of the chapter is to uncover the dimensions that doctoral training promotes: notably, the socio-emotional, artefactual and international dimensions that enhance the experience of young researchers and the support we provide them.

To conclude this introduction, I would like to note that the research covered in this volume is both modest and ambitious. The research is modest in that it focuses on a limited duration (six months) and involves only a dozen people within a given educational situation. But our project is ambitious by virtue of its openness: our research seeks to provide theoretical justification for a multidisciplinary approach to an object of research, a particular digital ecosystem. Based on the analyses that have been carried out, our project proposes new concepts that are suited to the realities and experiences described, to these situated “discursive technologies”. Our project also aims to contribute to the free and open dissemination of knowledge by way of the online publication of our results and by making the data freely available to the scholarly community.

Our research project constitutes both the culmination of a professional trajectory and the starting point for a multidisciplinary toolkit of digital interactions.

One volume: three reading levels

This volume provides three different levels of reading.

The first level provides a concentrated, synthetic version of the study. This is the “core” text, on a white background, which is also found in the paper version.

The second level, which is indicated by the open yellow text boxes, develops certain concepts for citations and for complementary analyses.

The third level, consisting of the yellow text boxes that have to be clicked open, provides more in-depth analysis using examples drawn from the data produced by the group: descriptions of key moments, transcriptions of interviews or conversations, videos, etc.