Research training in a polyartefacted doctoral seminar

Ethos and competencies of young researchers involved in collaborative work

Version

française >

Morgane Domanchin, Mabrouka El

Hachani, Jean-François Grassin, « Research training in a

polyartefacted doctoral seminar », Interactions and Screens in

Research and Education (enhanced edition), Les Ateliers de [sens

public], Montreal, 2023, isbn:978-2-924925-25-6, http://ateliers.sens-public.org/interactions-and-screens-in-research-and-education/chapter7.html.

version:0, 11/15/2023

Creative

Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0)

A major question in doctoral training is how to provide support for doctoral students in their appropriation of knowledge that is subject-specific and scientific as well as methodological and technical. As Isabelle Skakni (2011) notes, this training is often experiential, largely informal and unstructured. Doctoral training should be conceived as a process of socialisation to an academic career (Austin 2002), during which doctoral students appropriate a discipline-specific culture that William G. Tierney (1997) defines as a set of symbolic and instrumental activities specific to a given scholarly community. Which stages do doctoral students go through to become acculturated to an academic career and to be socialised? Doctoral seminars are one of the venues in which this process of acculturation and socialisation takes place. These seminars have the advantage of being spread out over a relatively long period of time during a doctoral programme, which reveals a certain progression in the construction of the doctoral student’s identity as a researcher.

When the “Digital presence” project was set up within the IMPEC seminar – a project in which the polyartefacted seminar itself was made the object of inquiry – we took the opportunity to study this process of acculturation and research training by way of research. The project entailed new modalities of participation by way of (1) the creation of an instrumented research apparatus and (2) self-reflexive research as part of a visual reflexive ethology approachCheck “Theoretical and methodological framework for visual reflexive ethology”.↩︎. We explore how the specific characteristics of the project configuring participation contributed to doctoral students’ training.

Students as agents

Students are active rather than passive participants in their learning and in managing their doctoral work (Jazvac-Martek, Chen, and McAlpine 2011). To this end, they actively seek out developmental experiences for themselves via the practices and groups in which they participate. But we lack knowledge about the types and nature of experiences that foster students’ learning and their identification with the role of researcher (Mantai 2015).

The aim of this chapter is thus to examine this form of collective work as a space of doctoral training by studying the process of acculturation. By identifying traces of personal engagement in the video data collected during the seminars and the interviews that followed, we investigate how participating in a polyartefacted seminar helps doctoral students develop certain professional and reflexive competencies through their collaboration on a joint research project.

Theoretical and methodological framework

The seminar, in combination with the “Digital Presence” project, was first and foremost a matter of training to do research by doing research, in that the doctoral students were expected to participate in all the stages of the project. The students’ participatory thinking, modes of behaviour and actions come together in these stages, developing their socio-technical and scientific competencies. The project was launched and piloted by Christine and was configured for her doctoral seminar, for both training and research.

Seminar framework

Following the framework that Christine adoptedChristine informed us about the framing of the seminar in e-mail exchanges.↩︎, we reproduce below the terms used to describe the ways in which the different dimensions of the training programme intertwined.

“Research training by doing research”: this idea is the equivalent of apprenticeships in jobs involving manual labour. Students learn by watching what others do and reproducing the same movements. The objective here is to interest the students in a project other than their own, but that will provide them with methodological tools which their own research can benefit from.

“Doctoral student participation”: our interest here was to give the doctoral students a role in the research group on the same basis as the other participants (researchers), even if the students had far less scientific experience.

“On the social level”: choosing the group as a training context was based on the assumption that surrounding doctoral students with people who are more advanced than they are in scholarly terms serves a heuristic function. The group, consisting of participants with different levels of knowledge, created the conditions for a zone of proximal development between doctoral students and postdocs in particular. In this respect we made sure that exchanges in the group took place in a safe atmosphere, in order to give the doctoral students the opportunity to express themselves, regardless of their level of knowledge on the subjects discussed. We also wanted to create a context that encouraged students to speak up and express ideas even if their critical thinking and self-confidence were not yet fully advanced.

“On a technical level”, doctoral students were often more at ease and more proactive than established researchers.

“On a scientific level”, bringing together colleagues from different disciplines and levels exposed doctoral students to new perspectives and offered them a broader methodological perspective than just the support of their supervisor.

The training programme also involved former doctoral students who had obtained their degrees and for whom this experience constituted a kind of “continuing education”. The programme also offered a discipline-specific and methodological opening toward linguistics for participating colleagues from other disciplines.

The seminar was designed to enable doctoral students to develop academic, technical and methodological competencies in collaborative situations that facilitated individual engagement and provided a supportive environment.

The seminar as a venue for developing specific competencies

In research training, Philippe Perrenoud (1995) underscores the importance of acquiring theoretical and disciplinary knowledge as well as “competencies related to the scholarly profession in a given discipline and in the corresponding organisations” (1995, 23). We explore the processes that help students need to acquire the competencies related to the academic profession which Perrenoud refers to. Few studies have been conducted thus far on the competencies acquired in doctoral training programmes, even if competency dictionaries are currently being implemented in Switzerland and Quebec.

Qualifications

In France, the doctoral degree has recently been added to the French National Directory of Professional Certifications (RNCP)More on the National Directory of Professional Certifications, or Répertoire National des Certifications Professionnelles (RNCP), which is managed by the organisation France compétences.↩︎, which places it at level 8 of the learning outcomes of the European Qualifications Framework (EQF)More on the European Qualifications Framework (EQF).↩︎ for lifelong learning.︎ The related competencies are described as follows:

The most advanced and specialised competencies and techniques, including for synthesis and evaluation, that are required to solve critical problems of research and/or innovation or to expand or redefine existing professional practices or knowledge (“Le doctorat enfin au RNCP !” 2018) Also see Le doctorat à la loupe, Confédération des Jeunes Chercheurs et Association Nationale des Docteurs, 2018.↩︎.

Competencies

Synthesising recent research, Claire Bonnard and Jean-François Giret (2016) describe five main categories of competencies:

Academic competencies specific to a field of research,

Organisational competencies,

Interpersonal competencies,

Project management competencies,

The capacity to solve unforeseen problems.

Three additional competencies can be added that correspond to our specific research situation: communicative competencies, collaborative competencies and semio-technical competencies related to the artefactual set-up. Setting up a research project focusing on the seminar itself as its object, with a special interest in its polyartefactual dimension, involved participants de facto in a project of co-construction. This provided them with a co-responsibility that was elaborated and carried out from one seminar session to the next through the constitution of a corpus and the construction of a research object. This very demanding form of personal engagement promoted the development of an academic ethos, and we examine how these competencies arose in self-reflexive discourse and over the course of the collaborative work sessions in the seminar.

The polyartefacted seminar as a collaborative situation

The learning situation that we are examining is in fact a highly collaborative situation. The definition of the word “seminar” in the French online dictionary Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé (TLFi) emphasises the collective and collaborative nature of this time devoted to discussion and exchange on a subject related to professional activity. For Wendy L. Bedwell et al. (2012), collaboration is “an evolving process whereby two or more social entities actively and reciprocally engage in joint activities aimed at achieving at least one shared goal” (Bedwell et al. 2012, 130).

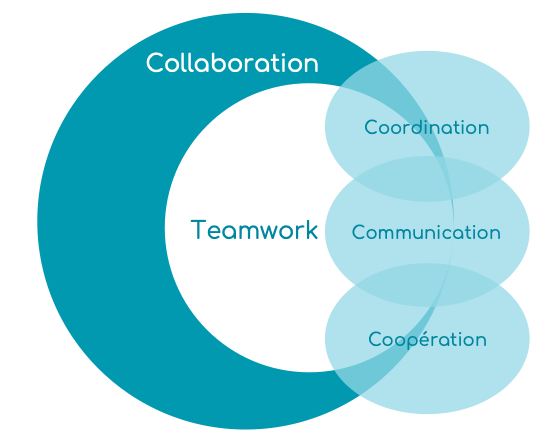

Representation of collaboration

Collaboration is an emergent and active process which is dynamic and constantly developing. We regard the social entities here as individuals with different professional statuses and roles. The collaborative process entails and articulates other processes such as coordination, cooperation and team building.

Collaboration, coordination, cooperation

These constructs are similar and sometimes used synonymously, but they represent somewhat different processes. “Collaboration”, first of all, is a complex process which can occur on different scales, involving different groups and at different times as well as multiple processes. We will describe joint work in general as a “collaborative practice”, but it is also a matter of “collaborative effort”: i.e., of moments when collaboration is the subject of discourse and requires planning that involves the construction of teamwork. Teamwork entails communication processes that rely on interactions among actors, resources (shared spaces) and acts of synchronisation. In our case study, Amélie, a doctoral student, raises the question of the quality of the data; this illustrates a collaborative effort deriving from collaborative practice.

Collaboration also involves moments of “coordination”, of “collaborative consultation”. Collaboration as a process entails the orchestration and synchronisation of activity, which is defined by Wendy L. Bedwell et al. in their review of the literature as “the interactive process by which individuals with differing expertise creatively resolve mutually identified issues” (Bedwell et al. 2012, 132). Note-taking, for example, illustrates this aspect in our analyses.

Finally, we refer to “cooperation” when the collaboration is conceived in terms of a dyad and a contribution to the joint task. As Bedwell et al. point out, the parties involved are supposed “to be concerned about the overall collaborative goal rather than their own individual goal” (Bedwell et al. 2012, 136). For example, when Morgane, a doctoral student, says that she is mainly concerned about whether all participants (ex or in-situ) are able to follow what the speaker is saying, she is adopting a cooperative posture.

As Mabrouka El Hachani explains, collaboration is the intertwining of these processes and entails “engaging in a joint action (cooperation), discussing this joint action (communication), and basing work on the organisation of interdependent tasks and actions that need to be carried out (coordination) to achieve the goal that has been set” (El Hachani 2014, 228). In this seminar, communication and coordination resources are highly polyartefacted. The doctoral training support organisation (Conférence Permanente des Directeurs.trices de laboratoires en Sciences de l’Information et de la Communication, CPDirSIC) notes that:

By being involved in the life of the research group, doctoral students acquire precise and up-to-date theoretical and methodological knowledge. Research units also provide a context within which doctoral students experience socialisation to academic professions, as well as other professions requiring a high level of expertise, such as when they are involved in contracts.

The seminar and the ethos of the young researcher

The collaborative situation of the seminar provided the opportunity to study the role occupied by the team’s doctoral students and the ethos they were constructing.

But which kind of academic ethos are we talking about? As Emmanuelle Leclercq and Danielle Potocki Malicet (2006, 1) note:

From the point of view of academic actors, there is not one academic profession, but many, which are largely structured by socio-professional membership, and a plurality of professional identities.

The array of academic profiles is quite rich, and it shows the degree to which the researcher is associated with a discipline or a research network or even a form of independence that is a described as a “professional career”. The authors point to an important distinction between academic profession and academic identity. If the former is common to all, the latter, on the contrary, leads to notable differences in the construction of professional identity as well as related work values. The question follows as to which models form the basis of the construction of the young researcher’s ethos.

Ethos

The collaborative situation allows us to study the place occupied by the team’s doctoral students, and the ethos they are constructing, in the collaborative activity of the seminar. The concept of ethos is studied particularly in linguistics and in the pragmatics of language (Amossy 2010), but also in the fields of education and professional pedagogy. In this study, we will use the definition of professional ethos proposed by Anne Jorro: “The way in which [people] organise their relationship to the professional world, how they define and redefine their field of action with respect to an ethical approach to the activity” (Jorro 2009). According to the author, this ethos borders on a quest for identity. We share the view that “the doctorate is as much about identity formation as it is about producing knowledge” (Green 2005, 153; Barnacle and Mewburn 2010) and that the doctoral seminar is the site of a social process of identity construction by way of the acquisition of certain roles. In the previous chapters, we have highlighted certain roles that are instantiated in collaborative actionSee, for example, the idea of instantiation in the chapter on “Artefacted intercorporeality, between reification and personification”.↩︎. Here we focus on the ethos of the researcher-in-the-making in their doctoral studies and, more specifically, during the challenge that the doctoral seminar represents. The concept of role in the sense of “situational involvement” (Cefaï 2013, 215) distinguishes between the role itself and the performance of the role:

Individuals get involved and are involved in-situations and their involvement is neither existential nor structural, but it is not entirely free either (Cefaï 2013, 215).

This is why we also rely on the notion of “role identity” (Jazvac‐Martek 2009). The theory of role identity posits that identity is a continuous process of social construction, which is based on an interaction between the social order and agents’ creative actions. This process is enacted via role identities that are formed as people categorise themselves, classify themselves, and associate themselves vis-à-vis a social group. In a situated and ecological approach, we need to distinguish between the notion of role and that of posture:

Whereas role is virtually defined in advance and imposes a certain type of behaviour, posture consists of an agile identity that is adapted to the context (Jorro 2009, 6).

Idealised roles are thus supported by the reactions or behaviours of other people and are performed in interaction. In this way, role identities, which we call postures, are dynamic. They evolve according to the context constructed by the expectations, motivations and actions of others, but also according to the way in which individuals present their intentions and react to what others bring into the interaction.

Social practice

Doctoral training is to be understood as a social practice (Lee and Boud 2009), and actors are still in need of processes of legitimation and self-verification. The characteristics of the processes of socialisation and identity construction can be revealed through an analysis of the collaborative activity entailed by the specific configuration of the polyartefacted seminar. Our analysis focused on enunciative postures in the students’ discourse in the reflexive interviews. “By organising a distribution of roles between interlocutors, the discursive ethos is believed to ensure a self-image in an intersubjective space riddled with values and norms and in which social interaction is experienced as something important” (Jorro 2013, 110).

In this chapter, we study how the identities of young researchers are constructed within a situation of polyartefactual collaboration by the student’s use of certain competencies. Our study analyses the competencies perceived and utilised by doctoral students in collaborative activities during the research project. Through our study of the discursive and pragmatic process of this construction in the action of the seminar, we present the concept of identity posture of legitimacy.

Methodology

In light of the fact that doctoral work is a poorly documented field as such, we adopt an ecological perspective to show its complexity. The four people conducting doctoral studies in the research team were not at the same stage of their thesis when the data was collected and the seminar was held. We hypothesised that this would have an impact on the expression of their academic ethos.

Table 1: Academic position of the four doctoral students in Lyon

| First name | Progress on doctoral work | Research group affiliation |

|---|---|---|

| Yigong | First year | ICAR (Interactions, Corpus, Apprentissages, Représentations) |

| Morgane | Second year | ICAR |

| Amélie | Third year | ICAR |

| Dorothée | Third year | ECP (Éducation, Cultures, Politiques) |

A cross-analysis of the reflexive interviews of the four doctoral students participating in the seminar and of the video recordings of the different sessions lead us to two types of analyses. We conducted both a content analysis examining epistemic postures, i.e., with respect to knowledge and competencies, and a discourse analysis of discursive enunciation and the construction of a discursive ethos (Maingueneau 2014) that distinguishes between “declared ethos (what speakers say about themselves) and observed ethos (what their manner of enunciation shows)” (2014, 34). The analysis of enunciative postures during the interviews reveals the construction of identity postures of legitimacy based on the collaborative situation and the individual’s identity as a young researcher.

Case study

The polyartefacted seminar as a conducive environments to doctoral training

We will now describe three general characteristics of the seminar that were conducive to doctoral training; then we will paint four individual portraits to show how students’ participation lead to their engagement in the project.

An extended space and time for doctoral training

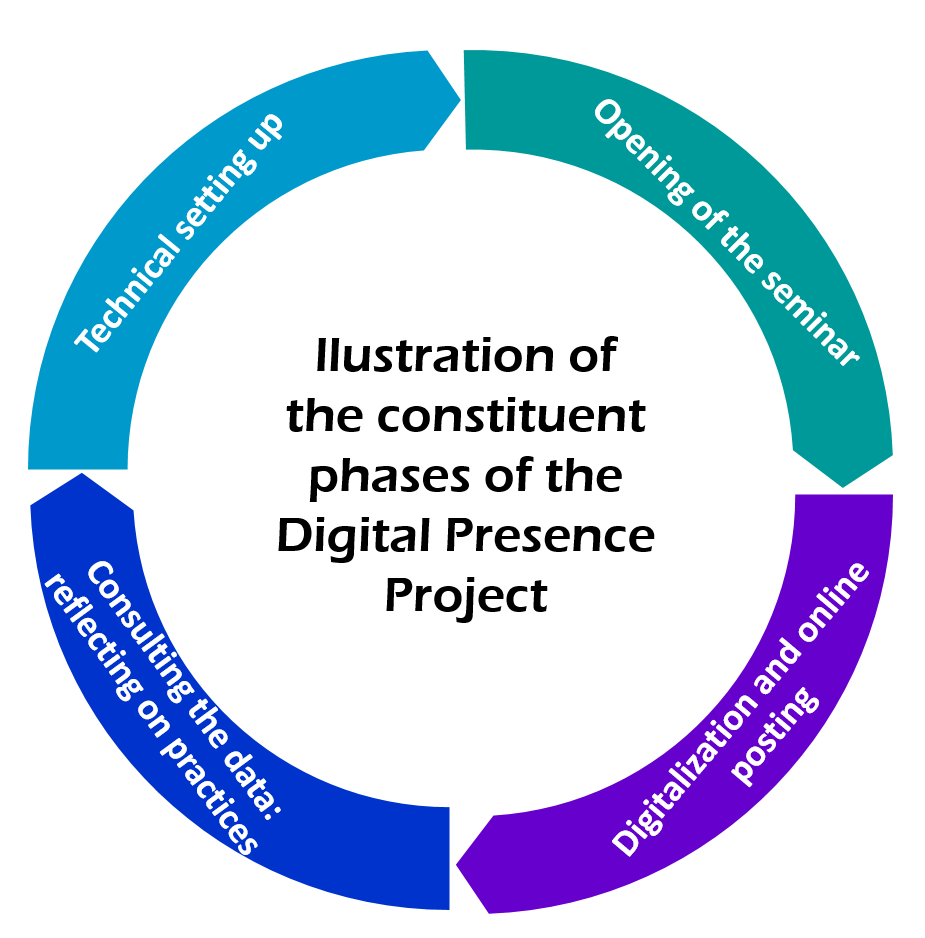

In comparison to the space and time constraints of a traditional doctoral seminar, the polyartefacted seminar has a more extended range. The doctoral seminar and the “Digital Presence” research project were marked by four different stages in time.

In the initial stage, setting up the seminar in technical terms presupposed a logistical installation involving the preparation of the telepresence artefacts and the material for collecting data.

The technical artefacts had to be set up for each session of the seminar to be able to take place. Once the artefacts were connected, in-situ and ex-situ participants were responsible for opening the proceedings when they arrived and also for bringing them to a close.

The data collected was then digitised and posted online: first in a private space shared by the members of the research team, and then, once the data was organised, on the Ortolang platform.

These two spaces allowed participants to consult the data.

Figure 2 : Illustration of the constitutive phases of the “Digital Presence” project

This diagram illustrates the four stages. These stages allowed for collective reflexivity and structured the research experience.

Complexified collaboration

As we have just seen, collaboration in the seminar was based on a complex apparatus.

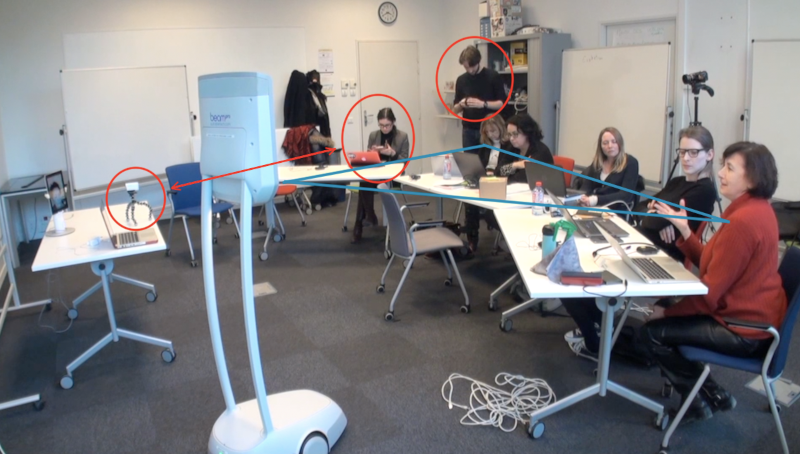

Multiple activities

Two activities can be distinguished on the screen capture below which shows a seminar session in January 2017 (Session 3): some of the members present in the seminar room are having a discussion (blue arrows) while others are looking at screens (red circles).

Two people, Morgane and Julien (red circles), are using their cell phones to adjust the frame of the camera – also in a red circle – which is on a table near the Beam robot. They are constructing a space of cooperation on-site, while another space of collaboration – represented by the blue triangle that shows the remaining members of the group talking with one another – is being developed by way of mutual listening. The seminar workspace supports multiple activities, governed by two parallel spaces of activity based on a form of attentional vigilanceCheck “Attentional affordances in an instrumented seminar”.↩︎ specific to each. The first space relates to cooperation in that it is a process of voluntary contribution to the shared collective activity. The second refers to collaboration that is characterised by communication among the actors about a common task. These tasks entail different communication devices used by the members who are present in the picture and involve bodies in different ways. Listening is different for each participant, and this can be seen from the posture of the hands holding the telephone, as well as their gaze and their head turned toward the screen and not toward another artefact or someone physically present.

The picture illustrates the intertwining of the synchronous communicative and interactional spaces involved in the joint project. Although the two activities in fact take place in parallel, they belong to one and the same script: that of the seminar.

The multiplicity of the spaces produced is a source of complexity and sometimes requires multple activities. But it can also be the source of more varied participation frameworks than in a traditional configuration, thus encouraging different forms of involvement that help develop the ethos of the young researchers.

Shared expertise

The polyartefactual dimension of the seminar imposed a novel dimension on all the participants, which appeared to be conducive to the inclusion of the doctoral students. For instance, as a researcher and the seminar coordinator, Christine’s expertise was acknowledged, but her status as “conductor” and her role in hosting guest speakers left the task of dealing with the research apparatus during the sessions to some of the participants. Over the course of the seminar, the technical competencies of the participants and, in particular, of the doctoral students were called upon in order to ensure that the technical set-up was working properly. As this set-up was complex and new to all the members, they shared responsibility for keeping it in good working order, and its highly technical dimension required complimentary forms of expertise. Depending on scientific or technical knowledge and competencies, participatory regimes were able to emerge which placed certain participants at the interface between different areas of expertise.

We will now illustrate the development of these competencies and analyse the postures of the four doctoral students in the seminar.

Identities of the junior researchers

Yigong

The traces of scientific and technical development that can be observed in the interviews conducted with the doctoral students vary depending on the situation of the doctoral student during the seminar as an in-situ or ex-situ participant. Yigong, a first-year in-situ doctoral student, described the seminar in his interview as a “new scientific experience”.

View of research

The novelty appeared to have a positive impact on his view of research.

It’s very enriching, I’ve never experienced any sessions like this where there are a lot of different kinds of technology in the seminar room; it’s very enriching to me, it’s more like an exploratory phase because I’ve never been to a seminar like this.

In his reflexive discourse, the French subject pronoun on (“we’) is rarely used; instead, Yigong uses”I” or a lexicalised third person plural (“the other researchers”, “other people”...) opposing him to the other members of the group, which could attest to difficulty in representing the group as a peer groupPrudence is required in the enunciative analysis of the interview, since French is not the doctoral student’s native language↩︎.

Meta vision

The “we/I” (on/je) dialogism constructed in the young doctoral student’s interview clearly expresses the posture that he is going to adopt throughout the research project, as reflected in the following verbatim extract:

At the beginning, for me, I didn’t really know what we were doing. But as time went on, when I finally figured it out [what we were doing], I knew a bit about the subject and also [I wanted] to explore it a bit, even if I haven’t really understood (laughs). So, in the end, I’m always curious about the research, about what we’re doing.

The personal pronoun on is used in a verbal expression that underlines the primacy of action: the seminar is about doing something together. Yigong indicates his involvement in the joint action undertaken. But the “I” allows him to express the way he is involved: Yigong lexicalises his introduction to research (“figuring out”, “explore a bit”), positions himself as someone who is learning (“I didn’t really know”, “I haven’t really understood”) and affirms his interest (“I’m always curious”). The doctoral student adopts the posture of a novice, but one who is active and involved. Over the course of his experience, as the analysis of the interviews shows, he seems to have developed a meta vision of the research project, from its development to its conceptualisation, by observing the polyartefacted seminar and the implementation of the research project. When talking about how the seminar helped him, he says that the “Digital Presence” research project allowed him “to discover… how to conduct scientific research”.

Although the topics covered were not directly connected to his thesisYigong is writing a thesis on digital literacy in the Chinese educational context.↩︎, Yigong says that he discovered “some concepts, but not a lot”. These discoveries led him to carry out internet searches while the seminar was going on, which sometime limited his participation in favour of note-taking.

Yigong’s notes

The notes taken during the seminar materialise the way in which participants position themselves with respect to the work of the group. Of the four doctoral students, only two, Yigong and Morgane, mention their note-taking in the interviews. The two doctoral students make the status of these notes explicit: they could be personal, shared or cooperative. Yigong refers to them as an essential part of his participation (“I focus on note-taking”), the aim being to understand what is going on in order to learn. But they are also a memorisation and work tool: “I reread my notes, I remember what I’ve seen during the speakers’ interventions”.

In the reflexive interview, this choice leads him to wonder about the nature of his participation in the seminar or rather of the other group members’ perception of him, in order to affirm his belonging:

For me I don’t feel like I’m absent, but I think, since I still don’t speak very well, I think for other people I am kind of absent from the seminar.

Member identity

Group member identity is constructed in interaction with the other members, since it requires legitimation, which is brought about in interaction. The seminar is a space of opportunities in the process of legitimating doctoral identity; the participants make use of this space in different ways. Through this space participants can confirm or test their identity roles, in light of the fact that these roles “are supported through the reactions or behaviours of others that act to confirm the person as an occupant of a particular social position” (Jazvac‐Martek 2009, 255).

Yigong explains what he means by “being present” and hence the actual actions that this participation entails:

Being present means... I feel, because I’m focused on taking notes and thinking about what is being said and sometimes on finding bibliographies, so I feel very present. Though I think compared to the others, I’m maybe kind of absent.

Validating identity

The notion of role identity is particularly useful, because it allows us to pay attention to both interpersonal experience (the way in which idealised role identities are verified or not) and intrapersonal experiences (the meaning and the expectations that are used to determine deviations from the identity of the idealised role). Here, the doctoral student does not perceive the validation of his group member identity by the other members. He explains the divergent expectations that are linked to this non-validation: the others are expecting oral participation in the seminar, whereas he prefers a different, more peripheral form of participation. In the two excerpts, the student wonders about his own participation and engages in a process of legitimation by affirming a “legitimate peripheral participation” (Wenger 2005). For him, this form of participation is related, above all, to personal activities (note-taking, web searches, reflection) as opposed to speaking, which he feels is an imperative and the primary recognised legitimate activity.

A first posture that can be identified in the interviews, and that we call an institutional legitimacy posture, is situated along a present/not-present axis. This posture is summarised by one’s own and others’ perception of one’s legitimacy in the group. Being present is being able to defend this legitimacy. In Yigong’s case, presence is so problematic that his concerns about this legitimacy are thematised in his reflexive interview. In the case of the three other doctoral students whose interviews will be analysed in the following sections, this takes place via the assertion of socio-technical competencies, which allow the student either to make herself present to others (Amélie) or to make all the members of the group present (Dorothée), or by a role identity as an interface between the groups (Morgane).

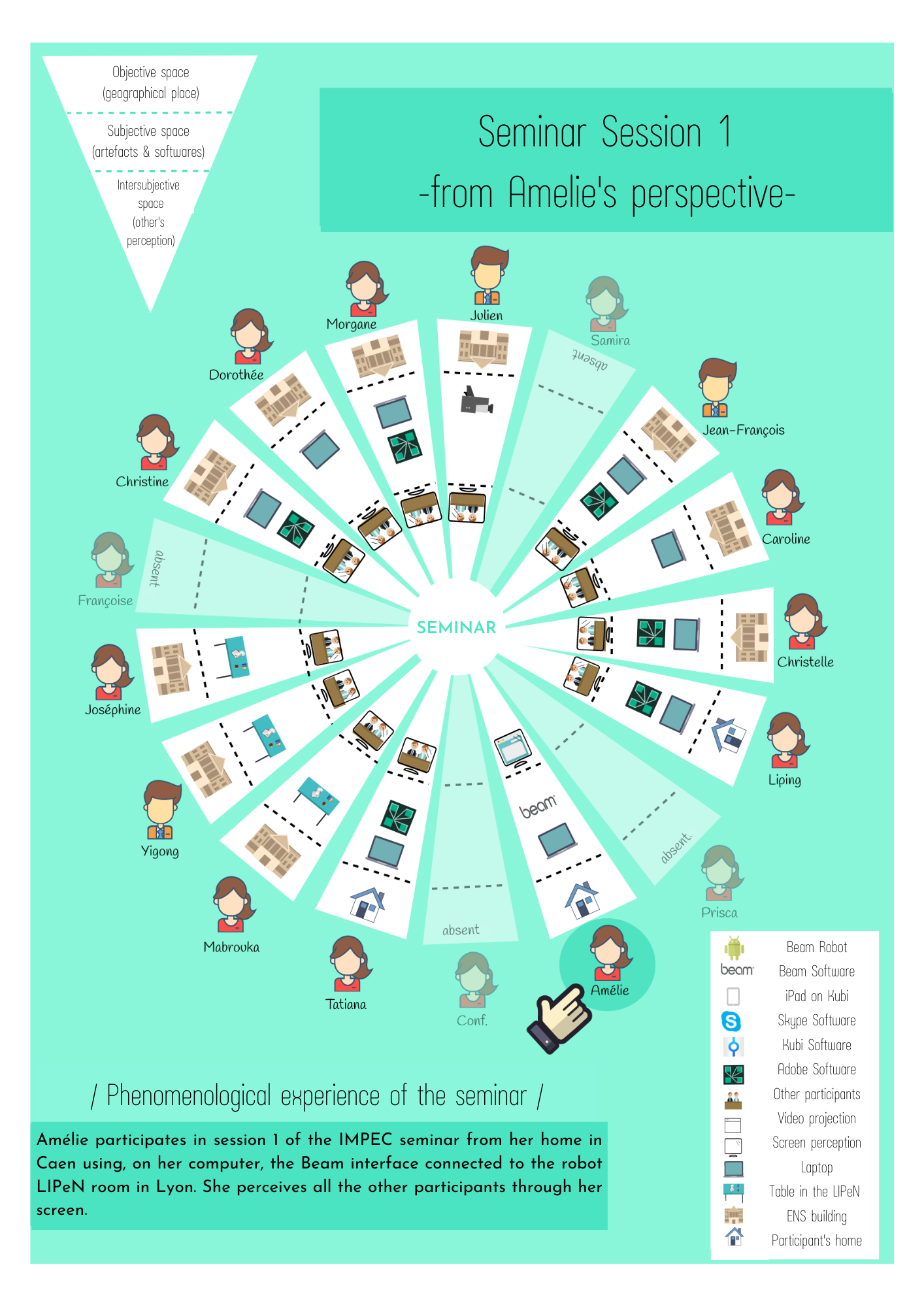

Amélie

Amélie’s posture within the seminar is constructed in a completely different way for two fundamental reasons: as a third-year doctoral student, Amélie is already working on telepresence robots and will participate in all the sessions using the Beam device. She thus forges an identity in the group via an artefactual presence and her developing expertise.

Figure 4: Seminar room in Lyon during the first session, as seen by Amélie in Caen

Avoiding technical difficulties

In the reflexive interview, she recalls the difficulties involved in participating via a telepresence robot and the different ways in which she was able to deal with them.

As she was alone and connecting remotely, the risk of isolation was significant and could give rise to uncomfortable and frustrating situations, which were not conducive to any learning at all and isolated her from the work team. As we see in the chapters on “New norms of politeness in digital contexts” and “Digital bugs and interactional failures in the service of a collective intelligence”, technical difficulties isolate the participant and may have an impact on the psycho-affective dimension of participation.

Amélie first recalls the strategies she had to develop to get around technical difficulties in order to be present and participate.

I don’t have any technical problems with the robot, so I think that can be a source of satisfaction; and, in any case, if I have a problem following along, I try to develop strategies. Like not being able to see the slide presentations, for example, or, in any case, I was looking at the slides projected on the wall, and I couldn’t see anything.

Explaining first that she doesn’t “have a problem” and is able to “develop strategies” for resolving problems, she affirms her technical competence. As Amélie is comfortable using new technologies, her regular use of the Beam robot allowed her to develop strategies to improve her audio and visual experience, since, with the Beam, she had difficulty seeing what was projected on the wall and the participants at the same time.

Ideas occur to me, strategies occur to me to be able to follow along in a way to optimise the system from my side in any case. For example, in the afternoon, when Dorothée gave her presentation, well I put myself in the Adobe [group] and, right away, I had the slides, I could have a slide window and a robot window to be able to see the people too.

She thus resolved the problem by connecting to the Adobe Connect telepresence interface. This technical strategy, which consisted of including herself in two systems (the Beam application and the Adobe Connect platform), lead Amélie to arrange her screen environment by dividing it into two parts, so as to see both the content projected on the wall during a presentation and the seminar participants.

Spatial isolation

The development of this technical strategy enriched the acquisition of competencies related to the use of the robot. This practice produced multiple foci of attention distributed over different parts of the screen and entailed the manipulation of two software interfaces. Amélie’s competence in mastering her remote presence was thus enriched due to the research apparatus itself. Amélie became aware of her difficulty in getting the floor via the robot when viewing the data a posteriori:

When I looked a little bit at the videos again, actually you can see that I start [speaking]She cannot see all the participants and hence cannot know whether someone is going to speak.↩︎. I have to repeat the beginning of my sentence maybe twice to get through; so either I insist [or] I wait for them to be nice enough to let me talk.

This growing awareness of her interactional practices (the need to cut off other participants and to repeat the beginning of her sentence several times) when she views the data allows Amélie to adjust her remote behaviour and to improve her interactional competencies in the artefacted seminar.

Amélie’s posture in the seminar is thus tightly connected to her artefactual presence. In her interview, a dialogic “I/they” (je/on) relationship appears in her discourse. In her interview, a dialogic “I/they” (je/on) relationship appears in her discourse. The first reason for this is the spatial isolation of the “I”, the on or “they” referring to the group physically present in the seminar room. What is at issue is a form of isolation within the research apparatus, and de facto in the group, due to the artefact (“they talk to me a lot in fact by saying the robot”), which places the “I” at the mercy of this “they” (“they give me a chance to talk”, “they ask me and I have nothing to say”, “there were things that were not necessarily satisfactory for me [like] where they put me to attend the afternoon session”).

The importance that Amélie attaches to resolving technical problems – to making communication more fluid in the group’s interaction by using technical competencies related to the manipulation of the robot and the software interfaces – can be explained by her desire to be involved in the research project. An inclusive “on” – in the sense of “we” rather than “they” – appears in her discourse and expresses her being part of the group of researchers (“for me it’s important actually to say that it’s properly framed because it’s important that we [on] have good data after all”, “what we [on] are doing has a certain scientific level after all”). This discourse shows both the participant’s difficulty and her desire to be fully involved in the situation, despite the distance and the (over)exposure entailed by her presence via the robot. The robot allowed her to be present but at the same time it also isolated and exposed her. The telepresence apparatus gave Amélie the means to be involved, but also entailed two correlated risks: isolation from the group and overexposure with respect to the position that she would like to have in it. For Amélie, the solution lay in the intensity of her engagement. She became involved in phases 2 and 4 of the project: the phase of holding the seminar, of course, but also the data visualisation phase – a retrospective activity that uses the research apparatus to increase competence by way of reflexivity.

Dorothée

The figure of Dorothée is in some ways similar to that of Amélie. Dorothée was also in her third year of doctoral studies during the seminar. She is a specialist in telepresence robots: her research deals with their educational uses. However, Dorothée was attended the seminar in-situ in her case.

One of the strategies employed by Dorothée to participate in the seminar was to assign herself a role in managing the technical telepresence apparatus.

Role regarding the interface

She thus explains the role that she gave herself over the course of the seminar, as shown below:

The camera, that’s my mission, I have the camera and given ... that I know the robot as well, as soon as there’s a problem with the robot I can either do some things concretely or make suggestions.

“Mission” and attentional load

In her interview, Dorothée affirms her technical expertise related to handling the Beam robot: she can “either do some things concretely or make suggestions”. This competency is also a scientific, since it is derived from her doctoral work. But above all, she assigns herself “a mission” during the seminar: that of managing the remote-controlled webcam that serves to retransmit the sound and image from the seminar room in Lyon to the remote participants. In her interview, Dorothée first recalls the difficulties related to the attentional load created by dealing with this artefact, which prevented her from following the seminar. She felt frustrated about not being able to follow the discussion and participate in it. But subsequently, due to technical habituation and repeating the movements over the course of the sessions, the webcam then becomes a “third eye”:

Now it’s a bit like my third eye because I do it... But yes, I have a quick look at the wall when we’re using Adobe, but I can tell from the camera’s ball-shape where it’s pointing, where its frame is; so finally now I can do that and take part in the discussion at the same time; actually it doesn’t require as much of an attentional load, it’s become very easy.

Dorothée’s repeated handling of the webcam allows her to focus less attention to it. Once she has acquired this technical competency, she is able to undertake several activities simultaneously and thus to become involved intellectually in the seminar. Dorothée clearly positions herself in a peer group. In her reflexive discourse, Dorothée uses the French on almost systematically in an inclusive way as “we”, such as to insist on the group’s cohesiveness (“we are among friends, we speak our minds”, “we know each other well”, “I remember that we were relieved”), on an emotional level in particular. The je or “I” is not opposed to the on, as for the two other young researchers, but is opposed to a “you” that is institutionalising and refers to the local institution hosting the seminar (“you are lucky to have this team”, “you have a good wifi environment at the ENS”).

An anecdote that she tells in the interview is revealing of the importance that she attaches to the construction of the scientific research and the role that she claims for herself. She explains that she was not physically present during one seminar and that the Adobe Connect system did not make it technically possible for her to intervene and defend her research personally.

Legitimacy

Dorothée was supposed to present an analysis that she had carried out with another group member. She claims that in the collective memory, this research was only attributed to the person who was present to defend it orally.

There were a lot of people who said that “ah Samira did a presentation last month, it’s Samira’s research”. And so I thought “well no, it’s also my research, but Samira said so in fact at the beginning, but I know that it had been interpreted [like]:”Dorothée wasn’t there, she wasn’t there to defend it”.

This was a decisive episode for Dorothée, and she refers to it repeatedly (“I wanted to say something because there were questions that I’d worked on”) while, at the same time, asserting her competencies (“I know what has to be done”), which leads us to conclude that the dominant posture in the researcher’s discourse is one relating to an epistemic knowledge that makes her competent and allows her to claim a place in the scientific discussion.

Dorothée claims a researcher’s identity related to her expertise, but, on this occasion, she does not manage to have it confirmed for technical reasons related to intervening remotely. The identity posture is thematised in her discourse along a “competent/incompetent” axis in scientific matters. But during this episode, the apparatus fails to make the participants equally present in the seminar. The apparatus thus interrupts the collaboration and isolates the young researcher, who finds this all the more difficult inasmuch she makes a very strong claim to her place in the peer group.

Morgane

Our last portrait is that of Morgane. Morgane plays a key role in the seminar, since she is involved in all four phases (preparation, holding the seminar, digitisation, and consultation of the data). In the “Digital Presence” project, she held the status of research assistant to Christine, who was her doctoral supervisor. This status gave her several responsibilities de facto. We will analyse the process of acquisition of competencies and her posture in three phases: (1) by examining her role as interface between the research team and the technical team responsible for collecting the data; (2) by examining her note-taking; and (3) by studying her legitimacy posture.

Morgane’s role of interfaceIn the interview, Morgane explains this role: “As for me, my function is really, so to speak, to be responsible for setting up the LiPen apparatus and also to be the technical support.”↩︎ between two teams involved taking into account the research objects during the phase of setting up the apparatus.

Role regarding the interface

My role in this case is really to act as an intermediary between the research team and the CCC teamThe Cellule (Complex Corpora Center) is the interdisciplinary team that supports the group’s research. Its missions involve collecting and exploiting so-called “complex” corpuses. The team was in charge of video recording the seminar sessions and also contributed to their digitisation and sharing.↩︎ ... since I was the intermediary, I was asked and what if we put the camera there so is that okay I had the responsibility even before we viewed the data of saying well okay there if we take into account the people who are interested in the robot, in the spatial movements, so I took the keywords of our seminar, so I could think up an apparatus that would be best suited to everything that we were thinking about doing.

This role required her to contribute to making technical choices by orienting and positioning the cameras depending on the research focus of each of the research subgroups being presented. During the data digitisation phase, choices were also made about multi-view video editing and were submitted to the rest of the research group. These choices, which had a considerable impact on the research, were made collaboratively by the two teams, but they had to be decided upon prior to the seminar. Since the other members of the research team were not necessarily present when these technical choices were made, Morgane had to explain the research objects to the technical team.

Morgane had a very strong sense of the spatiotemporal extension of the seminar.

Flow

It’s like [being in] a flow to me, the seminar doesn’t stop! And what’s more, the two seminar [sessions] were very close together, so it was even more difficult. But, in the end, between the emails we exchanged, our interactions, the design meetings, etc., the IMPEC LiPeN experience will have lasted the whole academic year for me finally, non-stop, we even talked about it in the hallways “oh yes, you did see my emails”, “oh yes I’ll send you a reminder”, “are you sure you’re going to be there to help me sett up the equipment”; it’s really a collaborative effort.

In her discourse, Morgane uses the French pronoun on in an extremely wide variety of ways. This proliferation of on and of its references in her discourse reveals a participant who is constructing her identity in belonging to various groups corresponding to different roles that she takes on during the research process.

Third role

First we find [a] an inclusive on, in the sense of “we”, which designates the collective of the seminar and which Morgane uses to make explicit her belonging to the group (“we talk a lot about the quality of the presence”, “we have roles whether we want them or not”, “we learned as we went along”).This on designates the participant in a group of peers.

Sometimes the on is not inclusive, but allows Morgane to make explicit one of the roles she took on in the research project:

they [on] didn’t force it on me which is why I say in quotation marks that the role was assigned to me because of the fact that I’m already working in the Cellule Corpus Complexes (CCC – Complex Corpora Center) with Justine, Daniel, etc.

This explanation allows her to interpret [b] a set of on, whose reference is the group that is responsible for the data collection set-up. Morgane moves from a third-person on (“they [on] gave me precise training with the cameras”) to a second-person plural on (“you [on] are going to prepare the equipment on diagrams you’re going to visit the seminar room, everything is predefined in advance”) corresponding to a role that Morgane claims and occupies (“you [on] put so much effort into it you [on] set up so many things that it’s disappointing when it doesn’t work”).

The co-existence of these two memberships in different groups [a] and [b] constructs a third role at the interface between the first two. Morgane’s identity role is explicitly that of an intermediary between two groups to which she belongs.

Morgane experiences the research project as a flow, she no longer distinguishes the technical discussions that take place outside the seminar, but that are an integral part of the research project. These discussions also illustrate the process of team building and of cooperation. The work team instantiates a form of collaboration involving individuals, and cooperation refers to individual orientation in a work team. Morgane is at the centre of this system of exchange between the Cellule Corpus Complexes (CCC)Complex Corpora Center.↩︎ and the research team that allowed the work team to be constructed. She cooperated with the CCC team for the purpose of the collaborative process.

Note-taking

The different roles played by Morgane entail reifying a number of exchanges, decisions and information in the form of notes whose status will allow us to understand both the competencies and the roles at stake. As the person responsible for ensuring that the polyartefacted set-up was working properly, she wrote personal notes or notes addressed to other members of the group, technical notes to facilitate the use of the apparatus and help to improve it:“They are technical specifications sheets there are two there is one for me and another for all of us that I post on Ortolang”, their purpose is to “resolve the problems we encountered so we can be more efficient the next time there is a problem”. Morgane affirms the importance of these notes within a process of technical cooperation.

As a research assistant, Morgane also takes “notes for [her]-self and for Christine”, “since Christine asks me to since when she is in the seminar she is occupying her position as conductor, she tells me that she sometimes finds it difficult to take notes ... so I simply suggested sending her my notes”. The notes have a dual status: they are personal and individual, but they also have to be shared. They are a means for inscribing her participation in the group research project via cooperation with the project director. This competency is established because “it’s internalised, it happens very fast”, she says.

References to two other note-taking spaces show that this form of participation has its limits and raise the question of the doctoral student’s legitimacy. At one point in the interview, Morgane mentions a note-taking space in which she is not participating:

I got some comments from Caroline who said Morgane why don’t you take part in the collaborative notes on Google Drive which is a word (sic) document which everyone can use to follow along.

Her explanation refers to a personal way of doing things, which she does not regard as suitable to collective exchange:

I don’t want to impose my way of taking notes on the collective document since, for example, there will be an “important ideas” section at the very start of my document with links and I don’t want to impose this in the collective document, for example, because maybe the others, when reading it, won’t find it interesting.

Later on in the interview, when the interviewer brings up the issue again, she adds an explanation related to her status.

I have the status of a second-year doctoral student in this seminar, I can only see myself sharing a collective document with doctoral students rather than with other people who have so to speak a superior academic status as assistant professor, teacher, professor. I would think that my notes are too basic.

In this excerpt, we see the path taken by the doctoral student’s reflections on how she could conceive of sharing notes with the collective and how the cooperation could be undertaken. This questioning is part of the pragmatic negotiations involved in the work of coordination, the acquisition of collaborative work competencies taking place in a dynamic way in a team.

The reification of collaboration constituted by note-taking allows us to read the ethos of the doctoral student, who is willing to cooperate, but for whom collaboration is still problematic. These shared spaces are symbolic spaces of positioning and practical spaces of transactive memory defined as a shared system that allows us “to encode, store and selectively retrieve the necessary information to conduct joint work” (Wegner, Erber, and Raymond 1991). They promote collaboration as a form of collective cognition to the extent that team members are conscious of where everyone’s expertise is located and agree upon the exact location. They tend to favour a horizontal posture among researchers, even if support is required in the case of junior researchers, as we just saw.

Intertwining digital spaces thus promotes both the production of scientific knowledge, by supporting collaboration, and research training, by varying the possibilities of participation.

Whereas the other doctoral students thematise their position in the seminar along a “present/not present” or “legitimate/not legitimate” axis, Morgane adopts a posture of legitimacy that is marked on the side of cooperation.

Interpersonal identity

Morgane clearly explains her highest priority role in the seminar: “As for me, I’m responsible for the technology and so my priority when there is a talk like that is for everyone to be able to follow along, to see and hear the speaker well”, or “I really make sure that all the participants can hear well”. This role appears in her discourse by way of numerous references to other members in a posture of legitimacy that highlights the interpersonal dimension and places doctoral identity along a “reliable/unreliable” axisWe understand “reliability” as a pragmatic legitimacy and we reserve the term “legitimacy” above all for scientific legitimacy.↩︎. She lays claim to recognition of this reliability from others or at least is worried about her ability to be and to be viewed as reliable. She claims that she needs to “show the others that [she] can handle such an apparatus”. She thus situates herself on the side of relationships with others, knowing that these relationships entails competence and trust. The price to be paid for this posture is reduced scientific participation (“I tend to fight to the end for the remote participants even if this means not listening to the talk at all”, “in terms of participation as a researcher it was low because as I said I was really trying to resolve the technical problem above all”).

We can note the appearance in her discourse of an “idealised” figure of the researcher who is able to participate in the scientific discussion, to make her voice and her knowledge heard whereas this is a figure that minimises the technical and material aspect of research for which the junior researcher is responsible. Now, the competency claimed by Morgane is this ability “to be able to propose solutions quickly, also to be able to judge the solutions proposed by others”.

We are thus able to observe via these illustrations how the format of the polyartefacted seminar invites participants to appropriate a variety of research, technical, scientific and collaborative competencies. When put into practice, they are always situated adaptive competencies.

Discussion

The seminar genreIn Yves Clot’s sense: “a sedimentation and prolongation of prior joint activities… which has been done by previous generations of a given milieu” (1999, 37).↩︎ and its expectations undergo renewal in a professional field both by virtue of its polyartefactual dimension, allowing for remote presence and creating spaces for complex participation frameworks, and by virtue of the support of a reflexive research project that promotes the development of socio-technical and scientific competencies and a rich disciplinary socialisation.

A supported training situation

During the the seminar, the doctoral students were given the opportunity to speak freely, in order to facilitate their integration into the group.

Freedom of speech

As Christine, who initiated the research project, recalls:

One of the things I’m happy about is that the doctoral students speak as much as the associate professors or the professors; I think it’s great to have this space for free speech.

As we have seen, this strong aspect of speaking up is imposed upon the doctoral students who have understood this fact and who are constructing their posture vis-à-vis this opportunity to be seized. The technical dimension on which the polyartefacted seminar is based is then added to this. This dimension requires specific competencies that some senior researchers do not always possess. The complementarity of competencies thus becomes essential for the smooth functioning of the seminar.

Expertise

Christine points out:

I recognise that I have, let’s say, a dominant expertise in the seminar. This is not at all the case on a technical level since there are other people who are much better at using the different tools than I am. So, it’s interesting because, on the one hand, this remixes the result of the interaction between different professional statuses and interpersonal relationships within the seminar. Because, in the end, the different areas of expertise were combined, and this also goes in the direction of what I’m trying to do most: i.e., to create a team with differentiated knowledge and competencies and that works towards a comprehensive product that is the result of all the competencies.

Taking into account the heterogeneity of the professional statuses of the participants, which is a classic element in the ecology of a doctoral seminar, is thus highlighted. But, above all, this calls into question the importance of a strictly scientific expertise for the purpose of training. Collaboration is constructed by way of the attribution of certain well-defined roles prior to the sessions, and these roles are supported by processes of cooperation over the course of the seminar.

Support

The doctoral student Morgane thus collaborated in the organisational and communicational dimension of the seminar by writing summaries that allowed the participants to follow how the collective thought processes were evolving and to progress towards the next stages of the research project.

Often, Christine would ask for a debriefing after each seminar on Monday ... So, she was the one as conductor who made the connection between the seminars. I take note of what she says to me, and I create reminders to myself; ... and what’s good about it is that she gives me deadlines that provide a continuity between all the seminars and when I send her my notes, it’s so that she can prepare the email she’s going to send to you collectively. And so often she sends me a first version of the e-mail that I review; I say [if] I agree [or] not, what needs to be changed. So, ultimately, this relationship between doctoral student and thesis supervisor does not run in just one direction. I see that I can contribute to things, it’s really win-win.

The individual support of her supervisor, which takes the form of cooperation, provides two different sorts of learning for Morgane: first, learning involved in synthetic note-taking on the exchanges that occur during the seminar and then learning how to frame a scientific project (time management, organisation of tasks...). Thinking is thus combined with action (the action of organising the seminar and communicating about it). This process allows the doctoral student to assume an active posture in her scientific and technical education. The doctoral student is attributed responsibility via this individual support, which she refers to as a “sign of trust” in the interviews, and she is given the opportunity to learn autonomously. The example reflects the reciprocity in the collaboration, which Morgane expresses as the “win-win” character of the work situation. Note-taking forms part of an extended coordination role as temporal orchestration and synchronises interactional dynamics, actions and tasks. This role is shared in a cooperative process.

The use of the French pronoun on in the reflexive discourse of the participants highlights how the speakers studied position themselves vis-à-vis a figure of the research group.

Enunciative postures

According to Christophe Dejours (1993), collaborative work involves the construction of “connections with a view to deliberately carry out a common work”. This discursive construction, which we summarise below, reveals how individuals weave these connections.

We can summarise the use of on in the following table:

| Yigong | Amélie | Dorothée | Morgane | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | - | + | + | ++ |

| Inclusive on | The research group, referring to the collective activity | The research group, referring to the collective activity | The peer group, referring to the horizontality of relationships | The research group, the peer group, the CCC group |

| Exclusive on | Versus remote “I” that is artefactually present | The conductor, the research group |

The enunciative postures are constructed in a dialogic

relationship between an inclusive on, which expresses belonging to a

group, and an exclusive on, which expresses the particularity of an “I”;

the identified instances of the pronoun on correspond to a positioning

of the “I” vis-à-vis the group. To inscribe oneself in this

collaborative work situation consists in constructing connections to the

others: connections via which the young researcher defines her position

in the group and with respect to her training. The doctoral students are

situated in an involving situation or, in a more complex manner, with

respect to what they do together and the roles they take on. This

inclusion in a collective implies its corollary, recognition by others

of an identity that will be defined by the instantiation of certain

roles that are seen to appear: the collective scientific activity of

research, the relationships among the members of the group that give

rise to a sense of belonging to the group, and activities of coordination among

sub-groups and members of the group.

These enunciative postures regarding the construction of a collective instantiation that is diversely expressed by on in the different forms of discourse thus have their complement in an analysis of “I” and the conditions of emergence of subjects by way of the enunciative affirmation of role identities or postures of legitimacy. We have identified three postures of legitimacy throughout our case study that make the doctoral student legitimate in the situation and that students develop via the utilisation of competencies:

a posture based on the legitimacy of presence, which we call on-site legitimacy posture;

a posture based on scientific legitimacy, which we call epistemic legitimacy posture;

a posture based on the legitimacy of the relationship to the other, which demands reliability and which we call pragmatic legitimacy posture.

By analysing discourse and action, we saw how these postures could be combined in a posture of multiple legitimacy, thus contributing to the doctoral student’s training.

Horizontality

In the previous analyses, we observe that the notion of being present at the seminar varies depending on whether one is in-situ or ex-situ. Thus, where the artefacts made available to Amélie could have reinforced her presence within the seminar via the Beam robotCheck “Attentional affordances in an instrumented seminar”.↩︎, the interview shows that she made increasing efforts to develop strategies to ensure that the remote connection was achieved in an optimal way for her. If a seminar is a space of communication in which speech circulates, having access to the opportunity to speak is far from being a simple matter. The horizontality of the points of view is not entirely apparent in the interviews; the participants measure the differences in levels and professional status. Their representation of the profession remains stuck in the dichotomy of senior researcher/junior researcher whereas the principle of the polyartefacted seminar was to attempt to make this vertical model disappear.

Conclusion

The doctoral seminar is the venue of the social process of construction of identity via the acquisition of certain roles and certain particular competencies, and this is all the more the case in a polyartefacted seminar. The specificity of polyartefactual seminar is that it is based on a relatively strong technical dimension, both in terms of remote communication and modalities of collaboration. In this configuration, the acquisition of technical competencies plays a key role in getting participants involved in the group, in particular, for doctoral students who are at an advanced stage in their training and who have a research topic closely related to the theme of the seminar project. The polyartefacted seminar promotes learning by doing and acting in real time and within a collaborative process. It also provides a reflexive, interdisciplinary space that promotes disciplinary openness for the doctoral students by multiplying the zones of proximal development.

Chameleon profile

Christine describes the polyartefacted seminar as relying on interdisciplinarity. This point appears fundamental in light of the complexity of current research issues, as well as the way in which research training should take this complexity into account. Frédéric Darbellay (2017, 4) writes about the profile of a researcher under construction:

A new profile of researchers whom we refer to as “interdisciplinary natives” (d) in the sense that they develop an interdisciplinary trajectory from the very start of their basic training, without a fixed disciplinary anchoring and whose research is spread over academic fields that include a broad sample of different disciplines. They are, so to say, born into and with a culture of interdisciplinarity.

According to Darbellay, the profile of these researchers is that of a “chameleon” given their capacity for adapting to the environment. In this sense, the polyartefacted seminar promotes many different sorts of learning due to a variety of zones of proximal development (co-organisation of the seminar with the thesis supervisor, preparation of the video collection tools and in-situ adjustments at the time of the recording with the technical support unit, etc.) that are generated by the process of collaboration. For Morgane, the polyartefacted seminar was an opportunity, by way of her dual status as a doctoral student and research assistant, to acquire multiple competencies (see Bonnard and Giret‘s (2016) five key competencies). This is how the doctoral seminar proposes an innovative configuration that is conducive to the co-construction of knowledge: i.e., collaborative learning. The doctoral students’ examples reflect the emergent feature of collaboration and how they became involved in it over time. They drew on their competencies to take an active part in a process of joint work. The development of these competencies contributed to the construction of their identity as a researcher.

This chapter examined the elaboration of a space of scientific discussion that is fundamental for research training. We have highlighted several salient points about the co-construction of this collaborative space and the processes it entails. Traces of the co-construction of group cooperation and the construction of work routines were emphasised and present evidence of a supported elaboration of research skills. Our study suggests that participation in a research project allows cultures and identities to develop that are key for research training (Sinclair, Barnacle, and Cuthbert 2014). The seminar is in fact “a performance, a practice, something that not only happens, in time and space, a choreography of bodies and voices, but is repeated, rehearsed and cited” (Green 2009, 248). This choreography allows doctoral students to observe and learn, and to develop competencies that are specific to the community they belong to. It is also a challenge in which the young researcher is anything but ontologically secure and which entails the creation of emotionally safe environments that the members maintain through the artefacted set-up and in being attentive to othersCheck “Attentional affordances in an instrumented seminar”.↩︎. The discursive ethos analysed here shows traces of this learning process and identity construction of the young researchers. Finally, the particularity of this type of research project, in which the participants take part in exercises of self-analysis (in the first and second personCheck “Theoretical and methodological framework for visual reflexive ethology”.↩︎), trains them for a subjectifying activity that is especially conducive to the construction of a critical and normative ethos.

Our study confirms the importance of others and self-validations in the construction of one’s identity as a researcher (Mantai 2015). These role identities in collaborative research are emphasised in different ways by the doctoral students, even if there are certain recurrent roles: the epistemic value of professional identity was found in the discourse of all the participants, some of them insisting on the problematic legitimacy that this identity entails for them. The identity as a researcher requires a participatory presence and a legitimacy for which they will need validation from other members of the group. For some, moreover, collaborative work in a polyartefacted situation seems to impose an identity that is validated in terms of reliability.

Finally, we showed the triple process-oriented heuristic aspect that is present in the situation: a doctoral seminar that is (1) scholarly, (2) highly artefactual, and (3) supported by a research project. This heuristic process interweaves the construction of ethos, apparatus and knowledge. Scientific and technical competencies are constructed along with the development of identity postures of legitimacy.