1Jocelyn Brooke (1908-1966) was an English writer and a literary critic passionate about botany and pyrotechnics. He authored the Orchid Trilogy (1948-1950), an autofictional work tracing the narrator’s development from his childhood in Kent to the Second World War. Brooke started writing in the 1920s and he rubbed shoulders with the bright young things satirized in the novels of Evelyn Waugh and Aldous Huxley. After a brief stint at Oxford University, seeking purpose, he rather improbably joined the army as a nurse during the Second World War. The Orchid Trilogy brought him some notoriety and allowed him to make a living from his writing. The Military Orchid (1948Brooke, Jocelyn. The Military Orchid, The Bodley Head, 1948.), A Mine of Serpents (1949), and The Goose Cathedral (1950) can be read as romans à clef and as chronicles of the British literary scene, from Decadence to late Modernism. This nostalgic text, characterized by a dense citational fabric, is the portrait of a writer in the making, driven by a desire that the central image of the orchid crystallizes.

2What accounts for the efficacy of this image? Does its power stem from the fascination exerted by the plant itself, or from the way in which its image circulates?

The Orchid Hunt

3Brooke wrote two botanical works, The Wild Orchids of Britain (1950Brooke, Jocelyn. The Wild Orchids of Britain, The Bodley Head, 1950.) and The Flower in Season (1952Brooke, Jocelyn. The Flower in Season: A Calendar of Wild Flowers, The Bodley Head, 1952.). Unsurprisingly, orchidomania drives the narrative of The Military Orchid. The seminal image of the orchid “appears” on the opening page when the narrator conjures a childhood memory, the “return” of a rare species, the Lizard Orchid, which is compared to a “comet” (1948, p. 1Brooke, Jocelyn. The Military Orchid, The Bodley Head, 1948.). A photograph of the orchid is subsequently published in the local newspaper, and the specimen is exhibited in the window of the photographer’s shop. Because the text entertains some confusion between the plant and its picture, the orchid is straightaway presented as the object of a double capture (by the camera and behind the window) and as the object of an unfulfilled desire. More apparitions and failed attempts at taxonomical identification follow. While similar flowers are discovered, one of the rarest species, the eponymous Orchis Militaris, remains elusive.

4This obsession has a long history. In the 18th century, the “orchid fever” encapsulated values associated with exoticism, rarity, and eroticism, which were still prevalent when Brooke wrote the novel. He projected these values onto the endemic specimens of the English countryside and Kent’s chalky landscapes. Although the local orchids are less luxuriant than their tropical relatives, they are similarly attractive and disturbing, haunting the narrator who associates the Orchis Militaris with the fantasized figure of the soldier. As a queer literary trope inherited from Aestheticism, the orchid is a symbol of guilty desire and of the writer’s quest.

The Migration of Images

5The “orchid fever” spawned a wealth of illustrated books and generated a literary and scientific intertext with which Brooke was familiar. In The Wild Orchids of Britain, Brooke presents himself as an amateur botanist offering an “Iconograph” of British orchids (1950, p. 8Brooke, Jocelyn. The Wild Orchids of Britain, The Bodley Head, 1950.). The project was conceived when Brooke and his childhood friend Gavin Bone (1907-1943) once drew a Lizard Orchid in 1924 (Brooke, 1950, p. 7Brooke, Jocelyn. The Wild Orchids of Britain, The Bodley Head, 1950.), the species that appears on the opening page of The Military Orchid. For his drawing of The Military Orchid, Bone copied Plate XLV of Henri Correvon’s Album des orchidées d’Europe (1899). After Gavin’s death, the plates of The Wild Orchids of Britain were completed by his father Muirhead Bone (1876-1953) and his brother Stephen (1904-1958), both of them war artists.

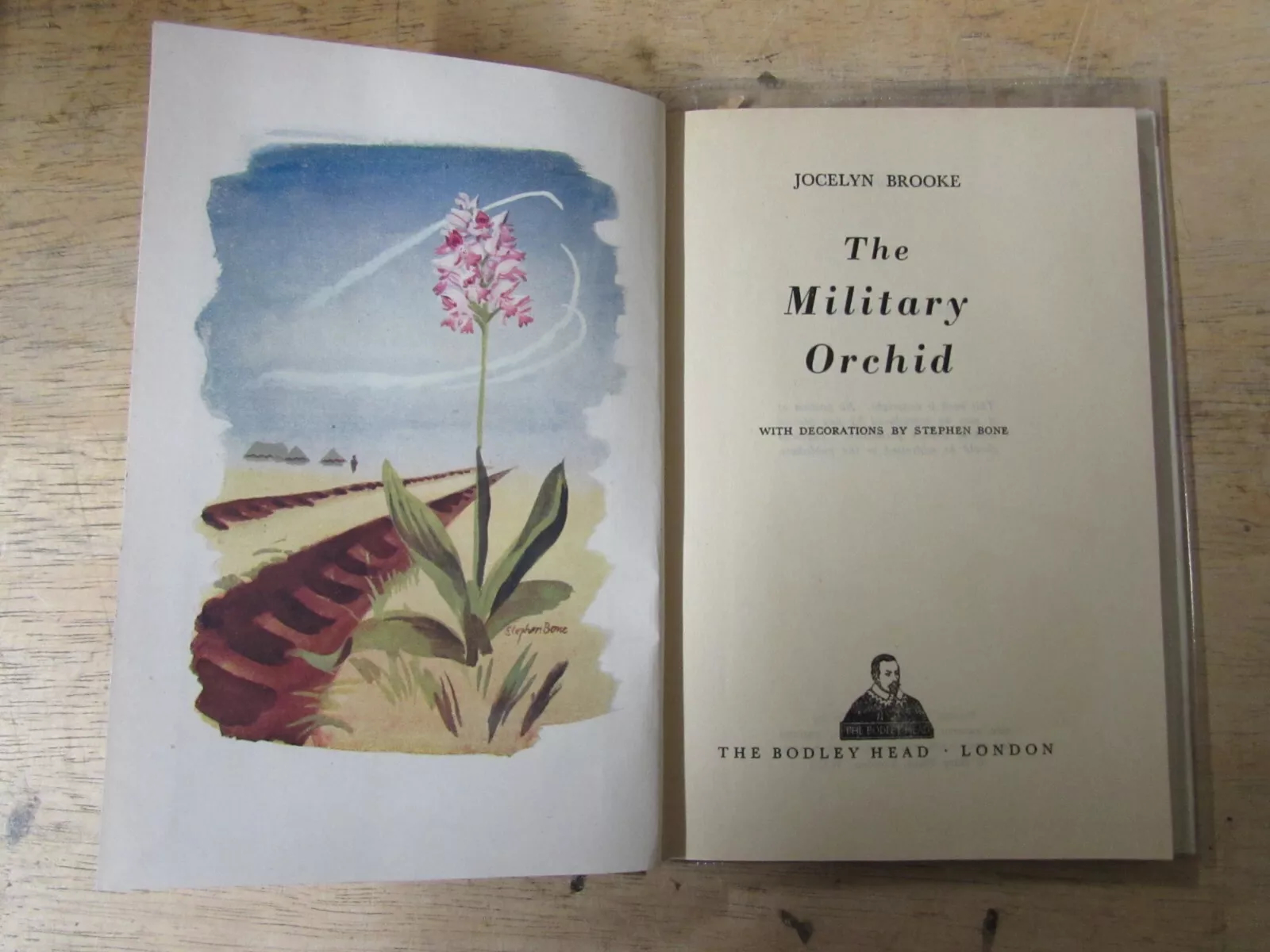

6Stephen also produced the frontispiece of The Military Orchid, a curious illustration depicting an orchid transplanted into a landscape that evokes the Battle of Britain as much as the Desert War in North Africa. This liminal picture shares the uncanny surrealism of the Blitz’s iconography. In the post-war period, bombed sites overgrown with plants became part of the English landscape and the recurrent appearance of orchids in the novel conjures spectral memories of the war.

7The proliferation of invasive plants is counteracted by Brooke’s taxonomic order. Yet, despite his love for scientific classification, his work crosses generic boundaries. Although the orchid he fetishized was threatened with extinction in his region, its image migrated from one work to another, from botany to the literary field. Such migration underscores the hybridity of his works. Thus, Brooke’s citational practice characterizes both the trilogy and its naturalist counterpart, The Flower in Season, his second “botanophile”’s work (1952, p. 11Brooke, Jocelyn. The Flower in Season: A Calendar of Wild Flowers, The Bodley Head, 1952.), which borrows the conventions of floras and florilegia. Like quotations, images circulate,allowing them to be reactivated instead of fading.

The Orchid and the Image-Act

8A seminal image that motivates Brooke’s text, a picture stemming from the material culture of botany, and a plant already threatened by environmental change, the orchid had lost none of its significance when Brooke’s trilogy was published. The fate of the orchid in our imaginary depends on its literary and botanical lineage, as well as on its migration as a picture — a reproducible artefactual image — and as a biological entity. The image-act resulting from the orchid’s agency ensures its literary survival. It participates in a movement of deterritorialization and reterritorialization that is specific to symbiosis in the living world. Brooke does not write a text about the orchid, but a text visited by the orchid whose charge of affect is thus replenished.

References

- Brooke, Jocelyn. The Flower in Season: A Calendar of Wild Flowers, The Bodley Head, 1952.

- Brooke, Jocelyn. The Military Orchid, The Bodley Head, 1948.

- Brooke, Jocelyn. The Wild Orchids of Britain, The Bodley Head, 1950.

- Correvon, Henry. Album des orchidées de l’Europe centrale et septentrionale, 1899.

- Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. Mille plateaux : capitalisme et schizophrénie. Tome 2, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1980.

- Endersby, Jim. Orchid: A Cultural History, Chicago University Press, 2016.

- Hoffmann, Catherine. “Jocelyn Brooke’s The Military Orchid: A Literary Hybrid,” Polysèmes. Revue d’études intertextuelles et intermédiales, no19, June 2018. https://doi.org/10.4000/polysemes.2531.

- Marx, William. Des étoiles nouvelles. Quand la littérature découvre le monde, Les Éditions de Minuit, 2021.

- Mellor, Leo. Reading the Ruins: Modernism, Bombsites and British Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2011.