1In her essay “A Portfolio curated by Rachel Kushner” (later published in

The Hard Crowd under the title “Made to Burn” (2021Kushner, Rachel. “Made to burn,” dans The Hard Crowd: Essays (2000-2020), Scribner, 2021, p. 113–136.)), American writer Rachel

Kushner unveils images that she collected while

writing her second novel, The Flamethrowers “A Meditation on that Stilled Image” (2014Kushner, Rachel. The Flamethrowers, Vintage Books, 2014.). The images in this

portfolio, intended to represent an artist’s work and

an archive of past inspirations, are accompanied by a short text. This approach contrasts with the five uncaptioned images in The Flamethrowers, the sources of which are listed at the

end of the book.

(2014Kushner, Rachel. The Flamethrowers, Vintage Books, 2014.). The images in this

portfolio, intended to represent an artist’s work and

an archive of past inspirations, are accompanied by a short text. This approach contrasts with the five uncaptioned images in The Flamethrowers, the sources of which are listed at the

end of the book.

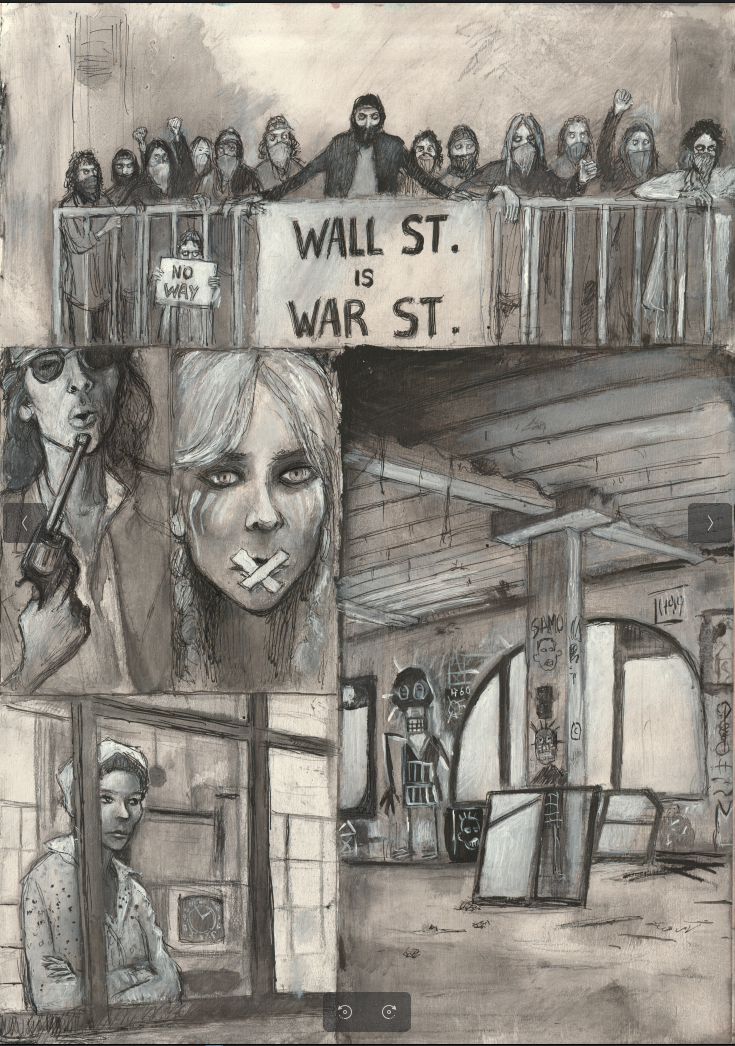

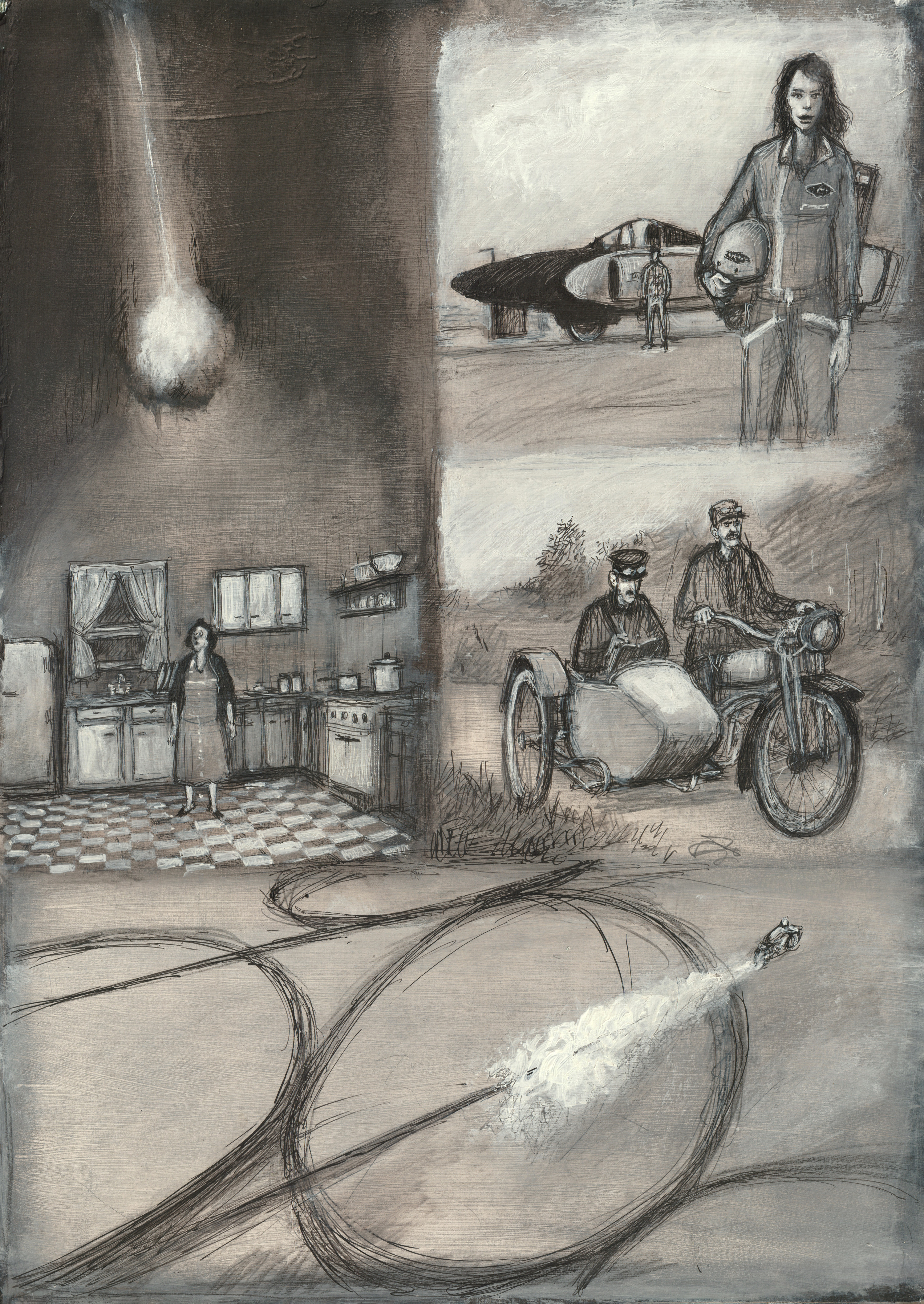

2This original illustration by Briac interprets and visualises some of the images that appear in Kushner’s writing. Regarding the role of pictures and the dialogic relationship between novel and images, Kushner reflects:

Why is it a photograph can disrupt the sheen of a text? The question itself leads me to want to include photographs in a novel. [.…] My novel opens outward. It deals with images, takes them seriously, is in dialogue with them. The images in the book are not illustrative — they are not meant to validate or justify — or to hamper. They are there to complicate or please, or hopefully both (Arnold, 2013Arnold, Drew. “The Rumpus Interview with Rachel Kushner,” The Rumpus, July 2013. https://therumpus.net/2013/08/07/the-rumpus-interview-with-rachel-kushner/.).

3These images are not mere inspirations or illustrations; in Kushner’s fiction, they act as counterpoints, generating webs of inferences and interferences, and creating moments of disruption in the narrative.

Imitation of Life: A Medium for Experience

4In The Flamethrowers, images are positioned on a left page, with the right page opening a new chapter. The uncaptioned images thus converse with the chapter titles, engaging the reader in a meditation on stillness and muted imagery. These images hold deep emotional resonance for Kushner, who observes:

An appeal to images is a demand for love. We want something more than just their mute glory. We want them to give up a clue, a key, a way to cut open a space, cut into a register, locate a tone, without which the novelist is lost (2021, p. 119Kushner, Rachel. “Made to burn,” dans The Hard Crowd: Essays (2000-2020), Scribner, 2021, p. 113–136.).

5Here, the act of incorporating images is described as a way to “cut open” the writing. The cover image of The Flamethrowers also appears in Kushner’s essay, where she explains:

The first image I pinned up, to spark inspiration for what could eventually be a novel, was of a woman with tape over her mouth. She floated above my desk with a grave, almost murderous look, war paint on her cheeks, blond braids framing her face, the braid a frolicsome countertone to her intensity (2021, p. 113Kushner, Rachel. “Made to burn,” dans The Hard Crowd: Essays (2000-2020), Scribner, 2021, p. 113–136.).

6If the first-person narrator of the novel is also a young blonde woman, both are rendered as “creatures of language, silenced”. The identity of the woman in the picture remains a mystery, leaving room for a “good story” (Kushner, 2021, p. 133Kushner, Rachel. “Made to burn,” dans The Hard Crowd: Essays (2000-2020), Scribner, 2021, p. 113–136.), allowing new voices to emerge from the still image.

7The first image the reader encounters in The Flamethrowers depicts a woman standing still behind a counter. It is a still from the 1970 film Wanda, directed by Barbara Loden. Kushner often cites the influence of films and their imagery on her writing, particularly Wanda:

It was a revelation to finally see [Wanda]. [.…] Maybe I see Wanda as being a particular kind of woman who is separate from the world, deep inside herself and yet open to being subjected to the world in a way I relate to. And so I was after the creation of a female who could embody something of what it is about Wanda that I recognize (The Open Bar, 2016The Open Bar. “A Psychotic Pattern of No-Pattern: A Conversation Between Rachel Kushner and Dana Spiotta,” Tin House, September 2016. https://tinhouse.com/a-psychotic-pattern-of-no-pattern-a-conversation-between-rachel-kushner-and-dana-spiotta.).

8The still from the film is placed next to a chapter entitled “Imitation of Life”, which focuses on Reno’s first alienating experiences in New York and its art world. Like Wanda, Reno wanders, seemingly passive, moving from one state or country to another and from one person to another. The protagonist’s narrative experience leans on a conductive transmission, which Kushner describes as “impressionistic” (Hart and Rocca, 2015, p. 202Hart, Matthew and Alexander Rocca. “An interview with Rachel Kushner,” Contemporary Literature, vol. 56, no2, 2015, p. 193–215. https://doi.org/10.3368/cl.56.2.193.). The narrator’s position mirrors Kushner’s within the art world, “listening to people be the raconteur”, collecting “the constant talking of human beings” (Owens, 2013Owens, Laura. “‘It’s spelled Motherfuckers.’—An Interview with Rachel Kushner,” Believer Magazine, May 2013. https://www.thebeliever.net/logger/2013-05-24-its-spelled-motherfuckersan-interview-with/.) and the images they created.

9This imitation of life is also echoed by the apparitions of real artists and surprising cameos, along with the intermingling of real-life references and images, which is playfully represented in one of the speeches Ronnie Fontaine gives to Reno while they are attending an art event in New York:

Larry Zox, Larry Poons, Larry Bell, Larry Clark, Larry Rivers, and Larry Fink. And they’re all talking to one another! This is some kind of historic moment (Kushner, 2014, p. 301Kushner, Rachel. The Flamethrowers, Vintage Books, 2014.).

10This passage reveals the referential playfulness of the novel: the names mentioned correspond to real-life artists (painters, sculptors, photographers…) who were contemporaneous with one another. Additionally, a photograph by Larry Fink is incorporated within the novel.

Capturing a World

11The photograph by Larry Fink, the third image the reader encounters in The Flamethrowers, is taken from inside a window display, showing members of the Black Mask collective in the streets holding a sign reading “WALL ST. IS WAR ST.” (2014, p. 184Kushner, Rachel. The Flamethrowers, Vintage Books, 2014.). This image appears next to a chapter entitled “The Way We Were”, in which the unacknowledged narrator, Burdmoore Model recalls his time and actions within the anarchist group “The Motherfuckers”. The same tensions of rebellion are also captured in a photograph by Tano D’Amico, At the Gates of the University. Kushner describes them as “remainders” of an “explosive era and its joys, traumas, and failures” (2021, p. 134Kushner, Rachel. “Made to burn,” dans The Hard Crowd: Essays (2000-2020), Scribner, 2021, p. 113–136.). The photograph shows students gathered at the gates of Sapienza University in Rome. In both cases, youth and revolt emerge as guiding forces, and these photographic representations, collected in The Flamethrowers and “Made to Burn”, connect disparate times and places.

12Another significant influence on Kushner is photographer William Eggleston (who is also an inspiration for a character in The Flamethrowers), whose “catalogue of images is like one enormous novel capturing a world, showing us the sly poetry and correspondence of things in casual repose” (Treisman, 2022Treisman, Deborah. “Rachel Kushner on Sharing a Car with a Stranger,” The New Yorker, April 2022.). Kushner includes in her essay a still from Eggleston’s Stranded in Canton (1974) depicting a man holding a gun. In the novel, the female narrator navigates a masculine world where artistic gestures symbolise “freedom, a realm where a guy could shoot off his rifle” (Kushner, 2021, p. 116Kushner, Rachel. “Made to burn,” dans The Hard Crowd: Essays (2000-2020), Scribner, 2021, p. 113–136.). The presence of this picture contributes at capturing a gesture. In contrast, another photograph by Danny Lyon (1967) of the inside of an abandoned warehouse captured “the vast demolition of Lower Manhattan” and “the death of American manufacturing” (Kushner, 2021, p. 123Kushner, Rachel. “Made to burn,” dans The Hard Crowd: Essays (2000-2020), Scribner, 2021, p. 113–136.). Demolition thus becomes the vector of artistic representations and performances that disturb the casual repose that can transpire from still images.

“A Surplus of Viewing”

13Capturing images within another medium reveals something more profound about their essence. Kushner notably mentions her fascination for pictures within pictures:

even as a child if there was a children’s book with paintings on the wall inside the image [.…] I always felt entranced, like I was seeing something more, a surplus of viewing that was not being controlled for presentation: as if the pictures inside the picture were ’real’ views, less authorized, because incidental (Owens, 2013Owens, Laura. “‘It’s spelled Motherfuckers.’—An Interview with Rachel Kushner,” Believer Magazine, May 2013. https://www.thebeliever.net/logger/2013-05-24-its-spelled-motherfuckersan-interview-with/.).

14This “surplus of viewing” motivates Reno’s artistic risks. During a demonstration in Italy, her camera breaks in the crowd, causing her to lose her art. Yet, she captures the sensation of merging with the crowd. The novel and its still images of riots and demonstrations preserve incidental moments of poignant suspension.

15The presence of images within Kushner’s writing, both fictional and nonfictional, thus offers profound insights beyond the text itself. Kushner’s image-acting encompasses “veiling, layering and fragmentation” forming a “collaborative work borne of variant subjectivities” (Worthy, 2016, p. 59Worthy, Blythe. “The Problem with Identity Politics: Dialogical Interrelation in Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers,” Philament: An Online Journal of Literature, Arts and Culture, vol. 22, 2016, p. 57–86.) and a “experiential constellation of intermedial, mediacy, and immediacy” (Kingston-Reese, 2019, p. 137Kingston-Reese, Alexandra. Contemporary Novelists and the Aesthetics of Twenty-First Century American Life, University of Iowa Press, 2019.). Kushner’s exploration of images and their effects transcends boundaries, creating a relational flow that fuses the written word with the stilled image.

References

- Arnold, Drew. “The Rumpus Interview with Rachel Kushner,” The Rumpus, July 2013. https://therumpus.net/2013/08/07/the-rumpus-interview-with-rachel-kushner/.

- Hart, Matthew and Alexander Rocca. “An interview with Rachel Kushner,” Contemporary Literature, vol. 56, no2, 2015, p. 193–215. https://doi.org/10.3368/cl.56.2.193.

- Kingston-Reese, Alexandra. Contemporary Novelists and the Aesthetics of Twenty-First Century American Life, University of Iowa Press, 2019.

- Kushner, Rachel. “Made to burn,” dans The Hard Crowd: Essays (2000-2020), Scribner, 2021, p. 113–136.

- Kushner, Rachel. The Flamethrowers, Vintage Books, 2014.

- Owens, Laura. “‘It’s spelled Motherfuckers.’—An Interview with Rachel Kushner,” Believer Magazine, May 2013. https://www.thebeliever.net/logger/2013-05-24-its-spelled-motherfuckersan-interview-with/.

- The Open Bar. “A Psychotic Pattern of No-Pattern: A Conversation Between Rachel Kushner and Dana Spiotta,” Tin House, September 2016. https://tinhouse.com/a-psychotic-pattern-of-no-pattern-a-conversation-between-rachel-kushner-and-dana-spiotta.

- Treisman, Deborah. “Rachel Kushner on Sharing a Car with a Stranger,” The New Yorker, April 2022.

- Worthy, Blythe. “The Problem with Identity Politics: Dialogical Interrelation in Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers,” Philament: An Online Journal of Literature, Arts and Culture, vol. 22, 2016, p. 57–86.